Editorials

How ‘The Entity’ Turned a Story of One Woman’s Suffering to Paranormal Propaganda– & Profit

The alternate title for this article was “Exploiting Abuse for Ghost Stories, Profit, And Fun”, but I figured that would be too much of a downer.

I am a skeptic about the paranormal. I always have been, and I probably always will be. Do I wish all ghost hunters out there would find something other than the occasional sparkly orb? You bet. Do I want the Mothman and all his precognitive, disaster-causing diva moments to be real? I have the themed sweatshirt to prove it. But I often find the most interesting cases of supernatural phenomena to be the ones with interesting people at the center of them. It’s why I can get invested in someone’s personal ghost story, but something that tries to take an objective stance usually fails to impress; the evidence is usually circumstantial at best and manufactured at worst.

Take for instance the Winchester Mystery House, which was the subject of its own film in 2018 inventively titled Winchester. I will always find myself enamored with how a house with a bizarre layout became the subject of supernatural speculation over the course of decades because journalists just went running with it. The idea that a house might have just been built complicated on accident because an unbelievably rich person made it, someone who couldn’t spend all of her inheritance in one lifetime and did so incompetently, is to me much funnier and more interesting than it being a maze for evil spirits.

And this is why, when a picture starts to form of the person investigating “objectively”, I lose the forest for the trees and really start focusing mostly on the investigator.

This is how I feel about the story behind 1982’s The Entity. It’s a solid supernatural film, but its effects and illusions, its brutal horror, and its harrowing ending pale when put up against the very odd real-life people the film is based on; it’s a spawning point of pseudo-science in the intrepid age of the 70s, the birth of two celebrity parapsychologists, and the story of how an abused woman’s suffering became a golden goose.

FROM TRUE STORY OF TERROR TO SUPERNATURAL CINEMA

The Entity is an adaptation of the novel of the same name, which is heavily based on the 1974 case of Doris Bither. A single mother of four living in Culver City, she reported being attacked by three invisible, demonic forces that repeatedly sexually assaulted her throughout her life. Disbelieved by almost everyone, she ended up accidentally running into two of the biggest parapsychologists of all time, Barry Taff and Kerry Gaynor, who made it their mission to discover the truth—her truth. Bither took her case to their pirate parapsychology laboratory operating out of UCLA’s main campus—not funded or approved of by the university itself, they were just renting space in the neuroscience building and doing whatever they liked in the name of supernatural research. They had a dark room and a dream, and by Jove, they were going to find some weird stuff out there.

The lab saw a lot of visitors because, given it was the Age of Aquarius and a lot of weird experimental stuff was going on with psychedelics and new-age spiritualism, everyone wanted in on the psychic phenomena the lab was exploring. Everyone from director William Friedkin to officials with the U.S. Army’s very own Stargate Project visited to try and get a look; the latter would be one of the many government projects that would serve as the inspiration for Stranger Things, Scanners, Firestarter, and pretty much every Stephen King character with the shining, so thank them for wasting taxpayer dollars but bringing us some cool media in the process.

BARRY AND KERRY’S BIG INVISIBLE BREAK

The chief investigators on the Bither case were Taff and Gaynor, who spent nearly 3 months returning to Bither’s house, a condemned building where they claimed to have objects thrown at them by spirits and suffered through rapid fluctuations in temperature. Bither’s dilapidated home was just one of the signs of her many years of struggle; she reported being abused as a child and suffered from addiction to various stimulants for much of her life.

The few photographs that survived the investigation are your typical affair. Orbs floating through the frame, arcs of light, all seemingly thought to be the three invisible assailants. Few actual photos made it out due to errors in processing the film, but it didn’t quite matter; Taff and Gaynor had much more titillating stories make it to the mainstream without pictures, such as Doris’s son putting on a Black Sabbath record that went so hard it caused baseball cards to levitate in the room.

Much like in the film’s very memorable and very haunting conclusion, Doris Bither never got her closure; by most accounts, she continued to be terrorized by the entities on and off, but they eventually visited with such infrequency she didn’t bother reporting it at all. She eventually lost contact with anybody who had been following the case altogether. Taff and Gaynor walked away from the investigation with more recognition, and author Frank De Felitta ended up making a worldwide best-selling novel of the events thanks to his correspondence with them and Bither. That book, The Entity, eventually became the film we know today, with Felitta adapting it into the screenplay which 20th Century Fox picked up. The rest is history.

The film’s main conflict is of course between our Doris proxy, Carla Moran (played by the unbelievably talented Barbara Hershey), and the singular Entity abusing her; though it was derided at the time for its exploitative scenes, many film scholars and fans find it a still relevant allegory for the force of sexual abuse on the psyche and the dismissal of sexual victimization among women who suffer it. I would have to agree. But the film also has what I believe to be some rhetorical goals related to the lab that the investigators belonged to.

UCLA VERSUS THE PARAPSYCHOLOGY LAB

Taff ended up being a technical advisor on the film, and it’s kind of obvious given the nature of his work and the way the plot is structured. It poses the characters of Sneiderman and Weber, the psychiatrist and university professor who deny Carla’s claims are supernatural, against Dr. Cooley (a stand-in for the real-life Thelma Moss who helmed the rogue parapsychology lab at UCLA and employed Taff and Gaynor). The movie does end in a way that villainizes Weber, as he runs away from the truth of the situation and elects to believe they suffered a mass delusion together. While the film doesn’t undercut the real Doris Bither’s story with a happy ending, it does very much paint the people who ran the university in a bad light.

I think the film has an agenda behind it, reflecting what I believe to be Taff’s personal beef with the university administration and those skeptical of his work. In another article, he identifies Dr. West, the head of the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute during the late 70s, as a man trying to “bury him” and the parapsychology lab for the media attention it was getting. The university had put them between a rock and a hard place, as they could no longer fund themselves and occupy the space in the lab; they were also unable to accept any grants for psychic research from government agencies on behalf of the university because the field is pseudoscientific at best, and donor funds being spent on that research could have damaged the school’s reputation severely.

He claims he had prophetic dreams of the shutdown, which do strike me as at the very least, resentful of the situation, if not the university as a whole given their apocalyptic nature; these dreams include mentions of Dr. West’s sister who had died of cancer being depicted as a decayed corpse and a doomsayer for the lab, which is struck by an earthquake in his nightmare. According to Taff, West never found out about the dream, and the lab was subsequently shut down in 1978.

In this light, the film feels like propaganda for all the Bither researchers involved. And Taff’s story provides great insight into how the lab has been mythologized, and why that propaganda is valuable. As much as Taff would like to act like they were silenced by West and UCLA, the parapsychology lab is still the stuff of legends thanks to the Bither Case and The Entity, as well as all of Taff and Gaynor’s own media appearances. To a good chunk of paranormal enthusiasts, they are still the rockstars of parapsychology. They saw a lot of success from the case, success that no sources indicate Doris Bither saw a share of. To this day, Taff is still a technical advisor for films and TV.

THE SANITIZATION AND SIMPLIFICATION OF THE DORIS BITHER CASE

As cynical as it is, part of me feels there is a desire to be propped up as the good guys here, in a very black and white way that denies the grey that is introduced by skepticism of their explanation. It depicts a university’s desire to avoid political and financial hot water as selfish. It paints the lab as a bastion of dangerous information, holding the keys to precognitive and telepathic powers. And it’s a symptom of something that gives me pause whenever I watch The Entity. It’s too clean of an answer.

I think the narrative of The Entity itself does sanitize the likely reality of what was happening to Doris Bither, ironically so given it is thematically screaming about everything that happened to her. I think it rejects the idea that Bither’s suffering could have been more complicated than ghosts; it minimizes the real horrors Bither went through, her substance abuse and likely C-PTSD from a trauma-filled childhood. It ignores the poverty she was living in for something much more comfortably frightening. It’s hard to face that societal and psychological conditions might be harder to tackle than spirits and monsters for most people. Even if they had gotten rid of the entities, what about all of her other problems?

I’m not trying to disparage Taff and Gaynor for their beliefs. Still, it stands to reason that the fame and recognition they got from celebrities, the media, and the government might have driven them to embellish details and benefit from missing materials. It might have encouraged them to make a complex woman’s life simple. And at the end of the day, nothing really is ever that simple. Few things ever end neatly, and the Bither case still resonates today because of that.

Because despite its relatively small impact on the cinematic landscape, The Entity is the farthest thing from simple when you get a good look at how it came about.

Editorials

Is ‘Funny Games’ The Perfect ‘Scream’ Foil?

When I begin crafting my reviews, I do some quick background research on the film itself, but I avoid looking at what others have to say. The last thing I want is for my views to be swayed in any way by what others think or say about a film. It has been at least 13 years since I’ve seen the English-language shot-for-shot remake of Funny Games. And I didn’t remember much about it. After watching the original 1997 masterpiece just minutes ago, I quickly ran to my computer to start writing this. Whether or not I’m breaking new ground by saying this is up in the air, and I could even be very incorrect with this: Funny Games is the perfect foil to Scream, and the irreparable damage it has caused to the slasher subgenre.

The Family at the Center of this Film

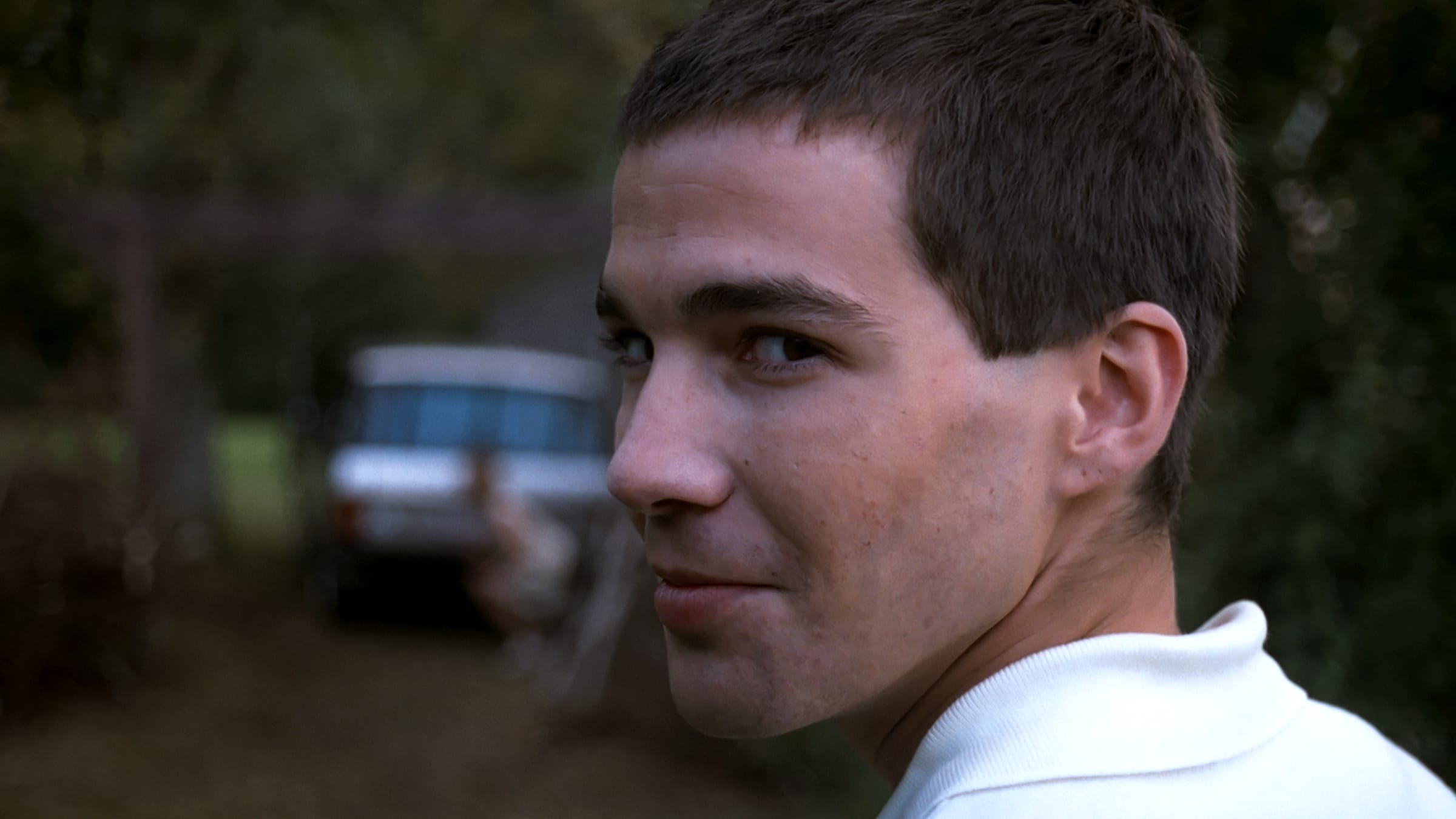

Funny Games follows the upper-class family of Anna (Susanne Lothar), George (Ulrich Mühe), son Georgie (Stefan Clapczynski), and dog Rolfi (Rolfi?), who arrive at their lake house for a few weeks of undisturbed peace. Soon after their arrival, they’re met by Paul (Arno Frisch) and Peter (Frank Giering), two white-clad yuppies who seem just a bit off. Who will survive and who will die in this game that is less funny than the title suggests?

I’ve made this statement about Scream time and time again. Before I get into it too much, let’s take a quick step back to ward off the Ryan C. Showers-like people. I love Scream (as well as 2, 5, and 6). It created a new wave of filmmakers and singlehandedly brought the slasher subgenre back from the dead like a Resident Evil zombie. Like what Tarantino did to independent crime thrillers of the 2000s and 10s, Scream has done to slashers. Post-Scream, slashers felt the need to be overtly meta and as twisty as possible, even at the film’s own demise. There is nothing wrong with a slasher film attempting to be smart. The problem arises when filmmakers who can’t pull it off think they can.

Is Funny Games Anti-Horror or Anti-Slasher?

The barebones rumblings I’ve heard about Funny Games over the years are that writer/director Michael Haneke calls it anti-horror. I would posit that Funny Games unknowingly found itself as more of an anti-slasher rather than an anti-horror. (Hell, it could be both!) Scream would release to acclaim just one year before Haneke’s incredible creation, so I can’t definitively say that Funny Games is a direct response to Scream, as much as I would like to.

Meta-ness has existed in cinema and art long before Scream came to be. Though if you had asked me when I was a freshman in high school, I would have told you Wes Craven created the idea of being meta. It just strikes me as a bit odd that two incredibly meta horror films would be released just one year apart and have such an impact on the genre. Whereas Scream uses its meta nature to make the audience do the Leonardo in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood… meme, Haneke uses it as a mirror for the audience.

Scream vs. Funny Games: A Clash of Meta Intentions

Scream doesn’t ask the audience to figure out which killer is behind the mask at which points; it just assumes that you will suspend your disbelief enough to accept it. Funny Games subverts this idea by showing you the perpetrators immediately and then forcing you to sit in the same room with them, faces uncovered, for nearly the film’s entire runtime. Scream was flashy and fun, Funny Games is long and uncomfortable. Haneke forces the audience to sit with the atrocities and exist within the trauma felt by the family as they’re brutally picked off one by one.

Funny Games utilizes fourth wall breaks to wink at the audience. Haneke is, more or less, trying to make the audience feel bad for what they’re watching. Each time Paul looks at the camera, it’s almost as if he’s saying, “You wanted this.” One of the most intriguing moments in the film is when Peter gets killed and Paul says, “Where is the remote?” before grabbing it, pressing rewind, and going back moments before Anna kills Peter. This is a direct middle finger to the audience. You think you’re getting a final girl in this nasty picture? Hell no. You asked for this, so you’re getting this.

A Contemptuous Look at Slasher Tropes

Both Funny Games are the only Haneke films I’ve seen, so I can’t speak much on his oeuvre. But Funny Games almost feels contemptful about horror, slashers in particular. The direct nature of the boys and their constant presence in each scene eliminates any potential plot holes. E.g., how did Jason Voorhees get from one side of the lake to a cabin a quarter of a mile away? You just have to believe! In horror, we’ve come to accept that when you’re watching a slasher film, you MUST accept what’s given to you. Haneke proves it can be done simply and effectively.

Whether you think it’s horror or not, Funny Games is one of the greatest horror films of all time. Before the elevated horror craze that exists to inflict misery on the viewers, Haneke had “been there, done that.” When [spoiler] dies, [spoiler] and [spoiler] sit in the living room in silence for nearly two minutes in a single uncut shot. Then, in the same uncut shot, [spoiler] starts keening for another two or three minutes. Nearly every slasher film moves on after a kill. Occasionally, we’ll get a funeral service or a memorial set up at the local high school for the slain teenagers. But there’s rarely an effective reflection on the loss of life in a slasher film. Funny Games tells you that you will reflect on death because you asked for death. You bought the ticket (rented the film), so you must reap what you sow.

Why Funny Games Remains One-of-a-Kind

This piece has been overly harsh on slasher films, and that was not the intention. Behind found footage, slasher films are probably my second favorite subgenre. As someone who has watched their fair share of them, it’s easy to see the pre-Scream and post-Scream shift. But there’s this weird disconnect where slasher films had transformed from commentary on life and loss to nothing more than flashy kills where a clown saws a woman from crotch to cranium, and then refuses to pay her fairly. Funny Games is an impressive meditation on horror and horror audiences. Even the title is a poke at the absurdity of slashers. If you haven’t seen Funny Games, I highly suggest checking it out because I can promise you, you’ve never seen a horror film like it. And we probably never will again.

Editorials

‘The Woman in Black’ Remake Is Better Than The Original

As a horror fan, I tend to think about remakes a lot. Not why they are made, necessarily. That answer is pretty clear: money. But something closer to “if they have to be made, how can they be made well?” It’s rare to find a remake that is generally considered to be better than the original. However, there are plenty that have been deemed to be valuable in a different way. You can find these in basically all subgenres. Sci-fi, for instance (The Thing, The Blob). Zombies (Dawn of the Dead, Evil Dead). Even slashers (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, My Bloody Valentine). However, when it comes to haunted house remakes, only The Woman in Black truly stands out, and it is shockingly underrated. Even more intriguingly, it is demonstrably better than the original movie.

The Original Haunted House Movie Is Almost Always Better

Now please note, I’m specifically talking about movies with haunted houses, rather than ghost movies in general. We wouldn’t want to be bringing The Ring into this conversation. That’s not fair to anyone.

Plenty of haunted house movies are minted classics, and as such, the subgenre has gotten its fair share of remakes. These are, almost unilaterally, some of the most-panned movies in a format that attracts bad reviews like honey attracts flies.

You’ve got 2005’s The Amityville Horror (a CGI-heavy slog briefly buoyed by a shirtless, possessed Ryan Reynolds). That same year’s Dark Water (one of many inert remakes of Asian horror films to come from that era). 1999’s The House on Haunted Hill (a manic, incoherent effort that millennial nostalgia has perhaps been too kind to). That same year there was The Haunting (a manic, incoherent effort that didn’t even earn nostalgia in the first place). And 2015’s Poltergeist (Remember this movie? Don’t you wish you didn’t?). And while I could accept arguments about 2001’s THIR13EN Ghosts, it’s hard to compete with a William Castle classic.

The Problem with Haunted House Remakes

Generally, I think haunted house remakes fail so often because of remakes’ compulsive obsession with updating the material. They throw in state-of-the-art special effects, the hottest stars of the era, and big set piece action sequences. Like, did House on Haunted Hill need to open with that weird roller coaster scene? Of course it didn’t.

However, when it comes to haunted house movies, bigger does not always mean better. They tend to be at their best when they are about ordinary people experiencing heightened versions of normal domestic fears. Bumps in the night, unexplained shadows, and the like. Maybe even some glowing eyes or a floating child. That’s all fine and dandy. But once you have a giant stone lion decapitating Owen Wilson, things have perhaps gone a bit off the rails.

The One Big Exception is The Woman in Black

The one undeniable exception to the haunted house remake rule is 2012’s The Woman in Black. If we want to split hairs, it’s technically the second adaptation of the Susan Hill novel of the same name. But The Haunting was technically a Shirley Jackson re-adaptation, and that still counts as a remake, so this does too.

The novel follows a young solicitor being haunted when handling a client’s estate at the secluded Eel Marsh House. The property was first adapted into a 1989 TV movie starring Adrian Rawlings, and it was ripe for a remake. In spite of having at least one majorly eerie scene, the 1989 movie is in fact too simple and small-scale. It is too invested in the humdrum realities of country life to have much time to be scary. Plus, it boasts a small screen budget and a distinctly “British television” sense of production design. Eel Marsh basically looks like any old English house, with whitewashed walls and a bland exterior.

Therefore, the “bigger is better” mentality of horror remakes took The Woman in Black to the exact level it needed.

The Woman in Black 2012 Makes Some Great Choices

2012’s The Woman in Black deserves an enormous amount of credit for carrying the remake mantle superbly well. By following a more sedate original, it reaches the exact pitch it needs in order to craft a perfect haunted house story. Most appropriately, the design of Eel Marsh House and its environs are gloriously excessive. While they don’t stretch the bounds of reality into sheer impossibility, they completely turn the original movie on its head.

Eel Marsh is now, as it should be, a decaying, rambling pile where every corner might hide deadly secrets. It’d be scary even if there wasn’t a ghost inside it, if only because it might contain copious black mold. Then you add the marshy grounds choked in horror movie fog. And then there’s the winding, muddy road that gets lost in the tide and feels downright purgatorial. Finally, you have a proper damn setting for a haunted house movie that plumbs the wicked secrets of the wealthy.

Why The Woman in Black Remake Is an Underrated Horror Gem

While 2012’s The Woman in Black is certainly underrated as a remake, I think it is even more underrated as a haunted house movie. For one thing, it is one of the best examples of the pre-Conjuring jump-scare horror movie done right. And if you’ve read my work for any amount of time, you know how positively I feel about jump scares. The Woman in Black offers a delectable combo platter of shocks designed to keep you on your toes. For example, there are plenty of patient shots that wait for you to notice the creepy thing in the background. But there are also a number of short sharp shocks that remain tremendously effective.

That is not to say that the movie is perfect. They did slightly overstep with their “bigger is better” move to cast Daniel Radcliffe in the lead role. It was a big swing making his first post-Potter role that of a single father with a four-year-old kid. It’s a bit much to have asked 2012 audiences to swallow, though it reads slightly better so many years later.

However, despite its flaws, The Woman in Black remake is demonstrably better than the original. In nearly every conceivable way. It’s pure Hammer Films confection, as opposed to a television drama without an ounce of oomph.