Editorials

Wendy Carlos Pioneer of Horror Movie Synth Soundtracks

NOTE: Since the publishing of this article 2 years ago, I have been made aware of some major mistakes and misinformation that were in its original iteration. A sincere thank you to Charlie Brigden, a freelance journalist best known for their work talking about film scores. They have informed me of the errors in this article on Wendy Carlos, and helped me amend them. My gratitude to them for helping make this article better, and my gratitude to you for reading. Thanks!

Some musicians actively strive to be the ones brought up in every conversation and fought for in every debate. Some of them even succeed. That some is John Carpenter. You can’t walk more than five feet into a talk about synth music without tripping and falling face-first into Carpenter’s oeuvre. And the reason for that has to do with the outrageous success he’s had in his primary medium: film.

Carpenter’s Lasting Influence on Modern Horror Films

Truly, Carpenter’s soundtracks are one of the first things that come up in any conversation about music in movies. Let alone music in horror movies which he dominated. Go to even his least successful horror film endeavors, and you will find nothing but heat.

For a good reason, I think there’s nothing quite like a Carpenter soundtrack, and many of the artists in the horror scene inspired by him would probably agree. Synth soundtracks emulating his style have since become all the rage with modern horror movies that call back to the 80s and 90s. Terrifier 2, Psycho Goreman, Mandy, The Guest, and It Follows are just what come to mind first. They’re the beginning of an exhaustive list of films with nostalgic synth soundtracks harkening back to his discography. So really, is there anybody who compares when it comes to his influence?

Wendy Carlos. The other some.

Wendy Carlos: Pioneering Electronic Music and Horror Scores

A brief introduction for the uninitiated: when it comes to electronic music, Carlos was the vanguard. Her magnum opus, Switched-on-Bach, is a collection of Bach pieces recreated entirely with the then-mostly unknown Moog synthesizer. The album was met with explosive commercial and critical acclaim for its never before heard innovation, and the Moog became an invaluable studio tool for musicians across the world.

She also became the first transgender Grammy award winner for Switched and by extension, one of the most prominent queer artists of the modern era. If Robert Moog was the man who crafted the ship, Wendy Carlos was the captain who steered it into the great unknown. She returned with untold riches, encouraging others to do the same.

You know, without a John Carpenter’s The Fog situation happening.

Carlos’ Overlooked Impact on Horror Cinema

Carlos has always been at the head of the line when discussing great modern composers. Still, I find that in casual conversation, she’s greatly overlooked and underrated for her influence on movies, particularly horror movies.

Carlos as an artist, and the Switched-on-Bach album, has been cited more than a few times by John Carpenter as one of his big inspirations, alongside bands like Tangerine Dream and the Italian horror mainstay Goblin. He is the way I found out about her in the first place.

After her work on Switched-On-Bach, she went on to produce the soundtrack to A Clockwork Orange, a film I would classify as psychological horror (but that’s a discussion for another day). Her cutting-edge reinterpretations of Beethoven and other classical musicians were the level of bold necessary for Kubrick movies. They perfectly engendered the horrors of Alex, his droogs, and the establishment around them. She built a soundscape that fit its mise-en-scene like a glove. And that was a feat she would replicate in another Stanley Kubrick classic she worked on.

Crafting the Iconic Sound of The Shining With Rachel Elkind

If scoring one of the greatest films of all time wasn’t enough, how about two? Proper respect is doled out in doses few and far between when it comes to horror, so let’s acknowledge her crowning achievement in cinematic scores: The Shining (1980), one of the greatest horror movies of all time.

This score was made in cooperation with her partner, Rachel Elkind, a classical musician, singer, and composer. In the original version of this article, I completely ignored Elkind’s massive contribution to the score, a failure of recognition that was unfortunately quite common according to Carlos herself. Rachel’s training as a jazz singer, her vocal range, and her style of musical composition complimented Carlos’ perfectly. It brought dynamism to their work in unexpected ways; her voice is even baked into the opening theme of The Shining, creating what Carlos described as the “sizzle effect” that permeates through the opening of the song.

The blend of music the two made is, frankly, inimitable. The Shining’s self-titled main theme is one of those songs that captures the tensest moments in the film. The piece has these inflection points that can send little noises into your ear and down your spine. The song is the voice of the Overlook and the first voice that speaks to you when you start watching.

A Symphony of Psychological Horror and The Lost Tracks of The Shining

It’s a neat reflection of the situation Stephen King penned and Kubrick adapted. The ghosts of the Overlook are a symphony of many players digging into Jack Torrance’s brain, and you are in the orchestra pit right with him. Carlos’ song embodies the gravity of being trapped in a horror that isn’t immediately apparent, becoming slowly and horribly aware of the overwhelming force you’re already standing inside.

There is one particular sound around the one-minute mark, this reverberating percussive force that shows up in the theme, that makes me want to look over my shoulder; sometimes, I even give in. It’s a fascinating, living noise with its own spirit, just like the hotel, and it is masterful.

Though much of Carlos and Elkind’s original work was shelved for the film and is hard to find outside of some very expensive CD copies, The Shining audio that is available will make your head spin. Carlos wrote the soundtrack to match the book before modifying it for the film, and its seamlessness is impressive. The teaser trailer for The Shining also contains the original “Clockworks (Bloody Elevators)” track that played during the infamous scene if you want a sliver of what could have been.

(P.S. I’m still miffed that it never made the final cut.)

Echoes in Modern Horror Scores

There are echoes of Carlos and Elkind’s work throughout modern horror film scores today. Take the acclaimed work of Colin Stetson in Hereditary, or Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow in Annihilation, or one of my favorites, Mica Levi’s unforgettable score for Under the Skin. All those soundtracks, and countless contemporaries, were touched by Carlos and Elkind.

And now here, in our new golden age of horror through the strange 2010s and roaring 2020s, the scores of a film are no longer a secondary aspect for your general audiences; it’s a deciding factor for many viewers. Bear McCreary for one, has lured me to many movies I wouldn’t have seen otherwise because his soundtracks are golden, and the fundamentals of what Wendy Carlos made run parallel to their works.

Yes, You Should Be Thanking Wendy Carlos

Not every musician is a fan of Carpenter, but most musicians owe Wendy Carlos something for her influence on modern music production, and it shows through the currents of inspiration that she cut indelible grooves into horror movie history.

Carlos famously began her most-seen interview on the Moog Synthesizer with the BBC by saying, “You have to build every sound. And to start to build these sounds, you have to start with something very simple.” While Wendy Carlos’ discography was by no means simple in creation or consumption, it is undoubtedly one massive spawning point, a tree trunk that branches out into the history of music.

And in terms of horror movie soundtracks, you’d be hard-pressed to find me another composer that deserves more credit. So, consider this that long overdue thank you we all owe her.

Editorials

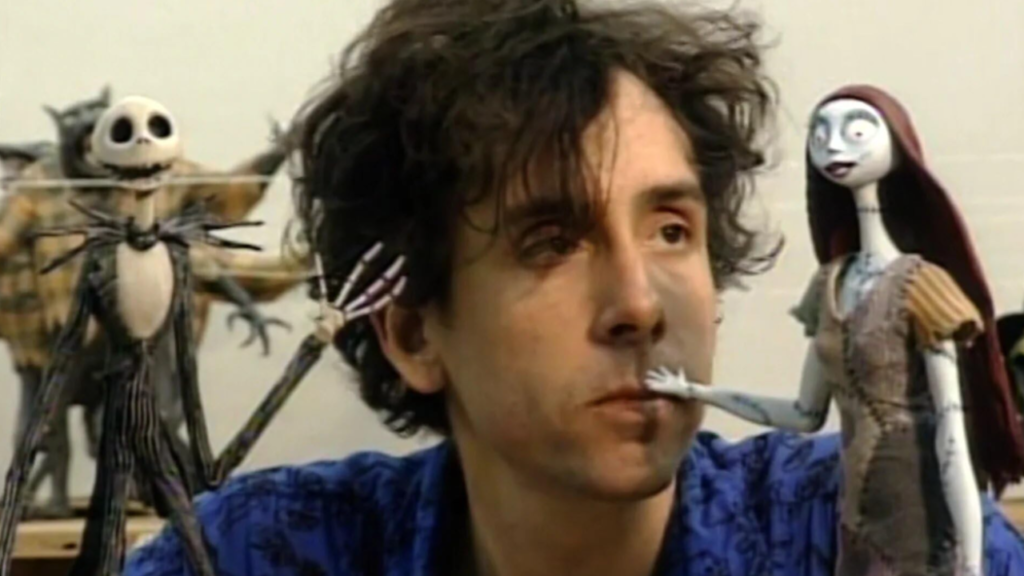

Tim Burton, Representation, and the Problem With Nostalgia

Tim Burton was not always my nemesis. In the not-too-distant past, I was a child who just wanted to watch creepy things. I rewatched Beetlejuice countless times and thought he was a lot more involved in Henry Selick’s The Nightmare Before Christmas than he actually was. I was also a huge Batman fan before Ben Affleck happened to the Caped Crusader. To this day, I still argue that Michael Keaton’s Bruce Wayne was one of the best. So when I tell you I logged many hours rewatching Burton’s better films in my youth, I am not lying.

However, as I got older, I started to realize that this director’s films are usually exclusively filled with white actors. Even his animated work somehow ignores POC actors, seemingly by design. This is sadly common in the industry, as intersectionality seems to be a concept most older filmmakers cannot wrap their heads around. So, I was one of the people who chalked it up to a glaring oversight and not much more. I also outgrew Burton’s aesthetic and attempts at humor when I started seeking out horror movies that might actually be scary.

I Was Over Tim Burton Before It Was Cool

So, how did we get to episodes of the podcast I co-host, roasting Tim Burton? I kind of forgot about the man behind all of those movies I thought were epic when I was a kid. In huge part because his muse was Johnny Depp, whom I also outgrew forever ago. I wasn’t thinking about Burton or his filmography, and I doubt he noticed a kid in the Midwest stopped renting his movies. I didn’t think about Burton again until 2016 rolled around.

In an interview with Bustle for Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, the lack of diversity in Burton’s work came up. That’s when the filmmaker explained this wasn’t a simple blunder or oversight on his part. He also unsurprisingly said the wrong thing instead of pretending he’d like to do better in the future.

Tim Burton said, “Things either call for things, or they don’t. I remember back when I was a child watching The Brady Bunch, and they started to get all politically correct. Like, OK, let’s have an Asian child and a black. I used to get more offended by that than just… I grew up watching blaxploitation movies, right? And I said, that’s great. I didn’t go like, OK, there should be more white people in these movies.” – Bustle

Tim Burton Is Not the Only One Failing

We watch older white guys fumble in interviews when topics like gender parity, diversity, politics, etc., come up all the time. It’s to the point now where most of us are forced to wonder if their publicists have simply given up and just live in a state of constant damage control. However, Tim Burton’s response was surprisingly offensive in so many ways. The more I reread it, the more pissed off at this guy I forgot existed after we returned our copy of Mars Attacks! to the Hollywood Video closest to my childhood home. While I knew I wouldn’t be revisiting Edward Scissorhands and Beetlejuice, his explanation for the almost complete absence of POC in his work burst a bubble.

We Hate To See It

Tim Burton’s own words made me realize so many obvious issues that I excused as a kid. Like Billy Dee Williams as Harvey Dent in Batman, it was the only time I remembered a Black actor with substantial screentime in a Burton film. Or that The Nightmare Before Christmas was really named the late Ken Page’s character, Oogie Boogie. As a Black kid, what a confusingly racist image with a helluva song. So, Burton saying the quiet part out loud is what led me to reexamine the actual reasons I probably stopped watching his work. His problematic answer is also why I don’t have the nostalgia that made most of my friends sit through Beetlejuice Beetlejuice.

I love the cast for this sequel we didn’t need. I am also delighted to see Jenna Ortega continue working in my favorite genre. However, from what I heard from most of my friends who watched the movie, I’m not the only person who has outgrown Tim Burton’s messy aesthetic and outdated stabs at jokes. I am also not the only one paying attention to what’s being said about the Black characters on Wednesday. Again, I’m always happy to see Ortega booked and busy. However, I also refuse to pretend Burton has fixed his diversity problem. If anything, this moves us deeper into specific bias territory.

Tim Burton’s Bare Minimum Is Not Good Enough

He will now cast a couple of Brown people, but is still displaying colorism and anti-Blackness. His “things” seemingly “call for things” that are not Black folks in key roles that aren’t bullies. He still feels that’s his aesthetic. If we are still dragging him into the last millennium, will he ever work on a project that truly understands and celebrates intersectionality? Or will he continue doing the bare minimum while waiting for a cookie? I don’t know, and to be honest, I don’t care anymore. I’m not the audience for Tim Burton. You can say my “things” no longer “call for things” he’s known for. In part because I’m over supporting filmmakers who don’t get it and don’t want to get it.

If a director wants to stay in a rut and keep regurgitating the mediocre things that worked for him before I was born, that’s his business. I’m more interested in what better filmmakers who can envision worlds filled with POC characters. Writer-directors that understand intersectionality benefits their stories are the people I’m trying to engage with. So, while Tim Burton might have had a few movies on repeat during my VHS era, I have as hard of a time watching his work as he has imagining people who look like me in his stuff. I will never unsee “let’s have an Asian child and a black” in his offensive word salad. However, I don’t think he wants me in the audience anyways because he might then have to imagine a world that calls for people who look like me.

Editorials

No, Cult Cinema Isn’t Dead

My first feature film, Death Drop Gorgeous, was often described as its own disturbed piece of queer cult cinema due to its over-the-top camp, practical special effects, and radical nature. As a film inspired by John Waters, we wore this descriptor as a badge of honor. Over the years, it has gained a small fanbase and occasionally pops up on lists of overlooked queer horror flicks around Pride month and Halloween.

The Streaming Era and the Myth of Monoculture

My co-director of our drag queen slasher sent me a status update, ostensibly to rile up the group chat. A former programmer of a major LGBTQ+ film festival (I swear, this detail is simply a coincidence and not an extension of my last article) declared that in our modern era, “cult classic” status is “untenable,” and that monoculture no longer exists. Thus, cult classics can no longer counter-culture the mono. The abundance of streaming services, he said, allows for specific curation to one’s tastes and the content they seek. He also asserted that media today that is designed to be a cult classic, feels soulless and vapid.

Shots fired!

Can Cult Cinema Exist Without Monoculture?

We had a lengthy discussion as collaborators about these points. Is there no monoculture to rally against? Are there no codes and standards to break and deviate from? Are there no transgressions left to undertake? Do streaming services fully encompass everyone’s tastes? Maybe I am biased. Maybe my debut feature is soulless and vapid!

I’ve been considering the landscape. True, there are so many options at our streaming fingertips, how could we experience a monoculture? But to think a cult classic only exists as counter-culture, or solely as a rally against the norm, is to have a narrow understanding of what cult cinema is and how it gains its status. The cult classic is not dead. It still rises from its grave and walks amongst the living.

What Defines a Cult Classic? And Who Cares About Cult Cinema?

The term “cult classic” generally refers to media – often movies, but sometimes television shows or books – that upon its debut, was unsuccessful or undervalued, but over time developed a devout fanbase that enjoys it, either ironically or sincerely. The media is often niche and low budget, and sometimes progressive for the cultural moment in which it was released.

Some well-known cult films include The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), Showgirls (1995), Re-Animator (1985), Jennifer’s Body (2009), and my personal favorite, Heathers (1989). Quoting dialogue, midnight showings, and fans developing ritualistic traditions around the movie are often other ways films receive cult status (think The Rocky Horror Picture Show).

Cult Cinema as Queer Refuge and Rebellion

Celebration of cult classics has long been a way for cinephiles and casual viewers alike to push against the rigid standards of what film critics deem “cinema.” These films can be immoral, depraved, or simply entertaining in ways that counter mainstream conventions. Cult classics have often been significant for underrepresented communities seeking comfort or reflection. Endless amounts of explicitly queer cinema were lambasted by critics of their time. The Doom Generation (1995) by Gregg Araki and John Waters’ Pink Flamingos (1972) were both famously given zero stars by Roger Ebert. Now both can be viewed on the Criterion Channel, and both directors are considered pioneers of gay cinema.

Cult films are often low-budget, providing a sense of belonging for viewers, and are sometimes seen as guilty pleasures. Cult cinema was, and continues to be, particularly important for queer folks in finding community.

But can there be a new Waters or Araki in this current landscape?

What becomes clear when looking at these examples is that cult status rarely forms in a vacuum. It emerges from a combination of cultural neglect, community need, and the slow bloom of recognition. Even in their time, cult films thrived because they filled a void, often one left by mainstream films’ lack of imagination or refusal to engage marginalized perspectives. If anything, today’s fractured media landscape creates even more of those voids, and therefore more opportunities for unexpected or outsider works to grab hold of their own fiercely loyal audiences.

The Death of Monoculture and the Rise of Streaming

We do not all experience culture the same way. With the freedom of personalization and algorithmic curation, not just in film but in music and television, there are fewer shared mass cultural moments we all gather around to discuss. The ones that do occur (think Barbenheimer) may always pale in comparison to the cultural dominance of moments that occurred before the social media boom. We might never again experience the mass hysteria of, say, Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

For example, our most successful musician today is listened to primarily by her fanbase. We can skip her songs and avoid her albums even if they are suggested on our streaming platforms, no matter how many weeks she’s been at number one.

Was Monoculture Ever Real?

But did we ever experience culture the same? Some argue that the idea of monoculture is a myth. Steve Hayden writes:

“Our monoculture was an illusion created by a flawed, closed-circuit system; even though we ought to know better, we’re still buying into that illusion, because we sometimes feel overwhelmed by our choices and lack of consensus. We think back to the things we used to love, and how it seemed that the whole world, or at least people we knew personally, loved the same thing. Maybe it wasn’t better then, but it seemed simpler, and for now that’s good enough.”

The mainstream still exists. Cultural moments still occur that we cannot escape and cannot always understand the appreciation for. There are fads and trends we may not recognize now but will romanticize later, just as we do with trends from as recently as 2010. But I’d argue there never was monoculture in the same way America was never “great.” There was never a time we all watched the same things and sang Madonna songs around the campfire; there were simply fewer accessible avenues to explore other options.

Indie Film Distribution in the Age of Streaming

Additionally, music streaming is not the same as film streaming. As my filmmaking collective moves through self-distributing our second film, we have found it is increasingly difficult for indie, small-budget, and DIY filmmakers to get on major platforms. We are required to have an aggregator or a distribution company. I cannot simply throw Saint Drogo onto Netflix or even Shudder. Amazon Prime has recently made it impossible to self-distribute unless you were grandfathered in. Accessibility is still limited, particularly for those with grassroots and shoestring budgets, even with the abundance of services.

I don’t know that anyone ever deliberately intends on making a cult classic. Pink Flamingos was released in the middle of the Gay Liberation movement, starring Divine, an openly gay drag queen who famously says, “Condone first-degree murder! Advocate cannibalism! Eat shit! Filth are my politics, filth is my life!”

All comedy is political. Of course, Waters was intentional with the depravity he filmed; it was a conscious response to the political climate of the time. So if responding to the current state of the world makes a cult classic, I think we can agree there is still plenty to protest.

There Is No Single Formula for Cult Cinema

Looking back at other cult classics, both recent and older, not all had the same intentional vehicle of crass humor and anarchy. Some didn’t know they would reach this status – a very “so bad, it’s good” result (i.e., Showgirls). And while cult classics naturally exist outside the mainstream, some very much intended to be in that stream first!

All of this is to say: there is no monolith for cult cinema. Some have deliberate, rebellious intentions. Some think they are creating high-concept art when in reality they’re making camp. But it takes time to recognize what will reach cult status. It’s not overnight, even if a film seems like it has the perfect recipe. Furthermore, there are still plenty of conventions to push back against; there are plenty of queer cinema conventions upheld by dogmatic LGBTQ+ film festivals.

Midnight Movies vs. Digital Fandom

What has changed is the way we consume media. The way we view a cult classic might not be solely relegated to midnight showings. Although, at my current place of employment, any time The Rocky Horror Picture Show screens, it’s consistently sold out. Nowadays, we may find that engagement with cult cinema and its fanbase digitally, on social media, rather than in indie cinemas. But if these sold-out screenings are any indication, people are not ready to give up the theater experience of being in a room with die-hard fans they find a kinship with.

In fact, digital fandom has begun creating its own equivalents to the midnight-movie ritual. Think of meme cycles that resurrect forgotten films, TikTok edits that reframe a scene as iconic, or Discord servers built entirely around niche subgenres. These forms of engagement might not involve rice bags and fishnets in a theater, but they mirror the same spirit of communal celebration, shared language, and collective inside jokes that defined cult communities of past decades. Furthermore, accessibility to a film does not diminish its cult status. You may be able to stream Tim Curry as Dr. Frank-N-Furter from the comfort of your couch, but that doesn’t make it any less cult.

The Case for Bottoms

I think a recent film that will gain cult status in time is Bottoms. In fact, it was introduced to the audience at a screening I attended as “the new Heathers.” Its elements of absurdity, queer representation, and subversion are perfect examples of the spirit of cult cinema. And you will not tell me that Bottoms was soulless and vapid.

For queer communities, cult cinema has never been just entertainment; it has operated as a kind of cultural memory, a place to archive our identities, desires, rebellions, and inside jokes long before RuPaul made them her catchphrases repeated ad nauseam. These films became coded meeting grounds where queer viewers could see exaggerated, defiant, or transgressive versions of themselves reflected back, if not realistically, then at least recognizably. Even when the world outside refused to legitimize queer existence, cult films documented our sensibilities, our humor, our rage, and our resilience. In this way, cult cinema has served as both refuge and record, preserving parts of queer life that might otherwise have been erased or dismissed.

Cult Cinema Is Forever

While inspired by John Waters, with Death Drop Gorgeous, we didn’t intentionally seek the status of cult classic. We just had no money and wanted to make a horror movie with drag queens. As long as there continue to be DIY, low-budget, queer filmmakers shooting their movies without permits, the conventions of cinema will continue to be subverted.

As long as queer people need refuge through media, cult cinema will live on.