Editorials

Finding Radical Queer Pride in ‘Tetsuo: The Iron Man’ (1989)

What if I told you Tetsuo: The Iron Man is one of the most evocative examples of “queer awakening” ever put on screen? Okay, that’s a tad hyperbolic, and such queer assertions about beloved media are often met with resistance, but in the case of Tetsuo, queerness isn’t just a supposition or mere subtext — it’s a hard-earned revelation.

That’s not to say Tetsuo is a coming-out story. At a film festival appearance in 2016, Director Shinya Tsukamoto expressed his motivation for making films around the time of Tetsuo as one of “exploring the link between cities and men and the relationship between society and humanity.” With Tetsuo, he emphasizes the dehumanizing impact of industrialized landscapes through the erotic fusion of metal and flesh. But the intimate scale of his production, limited cast, and use of settings largely in passing reveal a metamorphosis of a more personal sort through the shifting dynamics of its character relationships.

The demolition of the central character’s straight ego sends a salaryman (Tomorowo Taguchi) on a spiritual pilgrimage through emotions associated with grief (e.g., denial, anger, bargaining) before he embraces his inescapable truth. This arc is one that many closeted or once-closeted folks can relate to and perhaps sympathize with the internalized feelings this journey evokes — not unlike experiencing a death of the Self.

The most important casualty in Tetsuo is the version of himself that was shaped to fit society’s expectations of the norm. Only after letting go of this Self does he arrive at a hilarious yet hopeful conclusion: a steeling of his sensitivity against the pressures of others, and a militant acceptance of a queer mode of being.

Enter the Salaryman

Queering the norm comes easily when you start with the generic baseline of an office worker, as Tsukamoto does. The salaryman as a concept is a bastion of normality — one who is stably (though often nebulously) employed. Someone who slots right into the corporate machine, meets the minimum expectations as a productive member of society, and doesn’t challenge the status quo. But when Tsukamoto introduces his salaryman, the character is already in a state of torment and distress. He writhes and flails in a spotlight, flinging sweat as the movie’s title card scrolls to heavy, industrial beats.

An office worker is a role one might expect to receive some disdain from a filmmaker who was branded a failure and forced out of his family home for dedicating himself to independent art over gainful employment.2 But Tsukamoto doesn’t torture his salaryman without purpose. He aims to help the character transcend his conventional origins, deprogram his insecurities, and become stronger and more self-assured when all is said and done.

Flashback: A Fateful Collision

While we’re never shown the true nature of the salaryman’s profession, we do learn that he begins his journey of self-discovery while he is in an active relationship with a woman (Kei Fujiwara). Through carefully planted flashbacks, we see that the overzealous expression of their sexual love is directly to blame for their unfortunate collision with a pedestrian in crisis: the “metal fetishist” (Tsukamoto) whose hysteria over his body’s rejection of dirty, DIY metal implants sent him barreling into the couple’s path.

The pair awkwardly emerges from their vehicle, adjusting their clothes after their motor-borne tryst to dump the injured man among the trees. They then finish their sexual gratification in voyeuristic view of their unusual yet undead victim. Throughout their exhibition, the salaryman notably keeps his gaze squarely on the body of the unfortunate man — never on his partner — an early sign of a shift in his attention.

The significance of their victim’s metal affinity feels innately queer in comparison to the couple’s organic bond. Tsukamoto emphasized the eroticism of its symbolism in an interview with AsianMoviePulse.com where he stated, “I chose metal as a kind of fetish, because the electric brain and the human body becoming one with the metal is more like the act of making love, it has a strong sexual connotation.”

An Unfamiliar Self

Soon after this harrowing encounter in which a man, rather than a woman, first commandeered the salaryman’s focus, he awakens at home and attempts to proceed with life as usual, beginning his day with a fresh shave. The moment he steps in front of his mirror, he notices something has changed. A metallic “zit” appears on his cheek, which he quickly pops and covers with a bandage. This marks the beginning of his slip into unfamiliarity with the person he once envisioned himself to be.

It would be easy to write off this identity crisis as stemming from guilt over the surmised manslaughter and cover-up of the pancaked pedestrian whose dying vision was the couple in lust, but this simplification fails to capture the full scope of the shift in the salaryman’s relationship dynamics that the movie continues to explore.

Denial: A Creeping Suspicion

After the salaryman begins to question things he once knew about himself, he is thrust into a world where he must confront how he relates to others as well. On the way to his nondescript office job, he sits beside a bookish woman who is suddenly gripped by a metallic parasite that grants her a grotesque, metal claw. She becomes monstrous in the salaryman’s eyes and even chases him when he runs.

The pursuer corners him in an auto mechanic’s workshop, clutches her breast until it bursts, and speaks with the voice of the metal fetishist who should otherwise be rotting in a ditch. The salaryman’s hapless hit-and-run victim lives on, either as an obsessive figment of his guilt or somehow supernaturally revived in his grimy lair from where he remotely controls the parasitic claw’s host. The salaryman snuffs out the possessed woman with a full-body vice grip, then hurries home as his own metallic corruption courses further throughout his body.

The fact that this stranger is a woman is an important detail in this queer reading of the film. It forces our salaryman to confront a shift in his relationship with the opposite sex, lending fuel to the interpretation of a queer awakening. Defeminized through her possession by the fetishist, perhaps it’s not her womanhood that the salaryman wants to escape but rather the growing allure of metallic masculinity.

A Deadly Repression

But what of the salaryman’s attachment to his girlfriend? Their attraction is shown as highly sexual, but Tsukamoto seems to have hinted at cracks in their foundation from the moment their relationship was introduced. In the awkward phone call after the salaryman pops his metal zit, the lovers volley “Hello?” back and forth with little else to add. The salaryman seems far more engrossed in the newspaper than their call. Is he searching defensively for news about their crime, or is he perhaps hoping for a sign that the mangled man was rescued?

After his encounter with the stalker in the train station, the salaryman races home and dreams vividly of his girlfriend sodomizing him with a serpentine strap-on. While their physical relationship has shown significant freedom from prudishness, this is the first time we see a break from gendered norms. One has to question what the fantasy means for the salaryman as he grapples with the persistent allure of the metal fetishist.

Waking in a sweat, the two engage in desperate sex until the spread of his metal-morphosis painfully interrupts their act. As the couple recoups over breakfast, the salaryman is simultaneously aroused and perturbed by the heightened sounds of teeth meeting the metal utensils. He begs his girlfriend to promise not to leave him as he reveals the nature of his recent struggles.

In this moment, what the salaryman appears to fear most is abandonment for revealing his new truth, but one last attempt to mask or repress his physical and sexual condition leads to the impalement and untimely death of the final link between him and his former (i.e., straight) identity.

A Wake-up Call

As the body of his former girlfriend rests in the bathtub, the phone begins to ring. The salaryman — now almost entirely cast in metal — picks up the receiver, and the fetishist on the other end announces that he knows the salaryman’s secret. This prompts our salaryman to recall the collision that started him on his path of self-discovery — this time from his victim’s perspective. Afraid of being outed, the salaryman shoves a knife into an electrical outlet, but the shock only amplifies his metal-morphosis and creates an electromagnetic attraction that draws the metal fetishist to him.

The fetishist co-opts the girlfriend’s body and reconstitutes it as his own, appearing before the salaryman with a bouquet in hand. “Soon even your brain will turn into metal,” he says, crawling on top of the salaryman. “Let me show you something wonderful… a new world!”

In this moment, the salaryman finally recognizes a possible future in metal — one where he is not alone because the fetishist shares his brand of metallic disposition. But admitting as much would rewire all that the salaryman has known, and he flees in a panic one last time.

Tsukamoto addressed his fascination with anti-heroic characters like the metal fetishist (whom he often embodies in his films) in an interview with Variety.com. “In the beginning, the main character struggles and tries to avoid the path he is being sent down,” he said. “But the stalker awakes another side to his personality and pushes him towards being someone else. It’s fascinating to see something that is hidden inside someone.”

Bargaining: The Final Resistance

The salaryman begins to synchronize and sympathize with the fetishist. As he runs, he experiences visions of the car accident and past traumas that influenced the fetishist’s metal affinity, all from the perspective of his pursuer. While the salaryman’s own reformation is shiny, untainted, and new, the fetishist’s metallic nature is rusted and impure, which could perhaps be attributed to the solitary, unsupported nature of the fetishist’s own path to self-discovery.

Their chase ends in a heap of metal. The salaryman’s new reality can no longer be denied. The fetishist decides to end the salaryman’s anguish, but the salaryman has come to terms with his new reality and refuses to enter his “new world” alone. With a deep, pelvic thrust, he assimilates the fetishist into his being — solitary trauma and all.

Radical Acceptance

The salaryman finally accepts his position outside the conditions that society once placed upon him, and now he does not have to live in fear of the future alone. Tsukamoto leaves no ambiguity to the nature of the salaryman and the fetishist’s intimacy with his image of the pair nude and joined at one hand with a metal cuff. Their bond is inseparable. In a flash, the two are transformed into a phallic tank, ready to make their vision of a “New World” a reality through radical, shared pride.

While this analysis examines one particular journey through identity, no journey of self-discovery is identical. For some, growing into a new identity is a slow burn. For others, it may be a sudden upheaval, as with the leap of a frenzied pedestrian into their life’s trajectory. Whether someone is gay, bisexual, or even a budding artist in a family of doctors, there’s something about the salaryman’s journey that can speak to anyone who has contended with the pressure of meeting the expectations of others before their own, and that’s precisely what I love about this gloriously weird movie.

May we all take pride in who we are and wreak our own brand of reconstructive havoc on an unjust world. As the metal fetishist so gleefully declares, “Our love can destroy this whole fucking world!” (Penis panzer optional.)

Editorials

Is ‘Funny Games’ The Perfect ‘Scream’ Foil?

When I begin crafting my reviews, I do some quick background research on the film itself, but I avoid looking at what others have to say. The last thing I want is for my views to be swayed in any way by what others think or say about a film. It has been at least 13 years since I’ve seen the English-language shot-for-shot remake of Funny Games. And I didn’t remember much about it. After watching the original 1997 masterpiece just minutes ago, I quickly ran to my computer to start writing this. Whether or not I’m breaking new ground by saying this is up in the air, and I could even be very incorrect with this: Funny Games is the perfect foil to Scream, and the irreparable damage it has caused to the slasher subgenre.

The Family at the Center of this Film

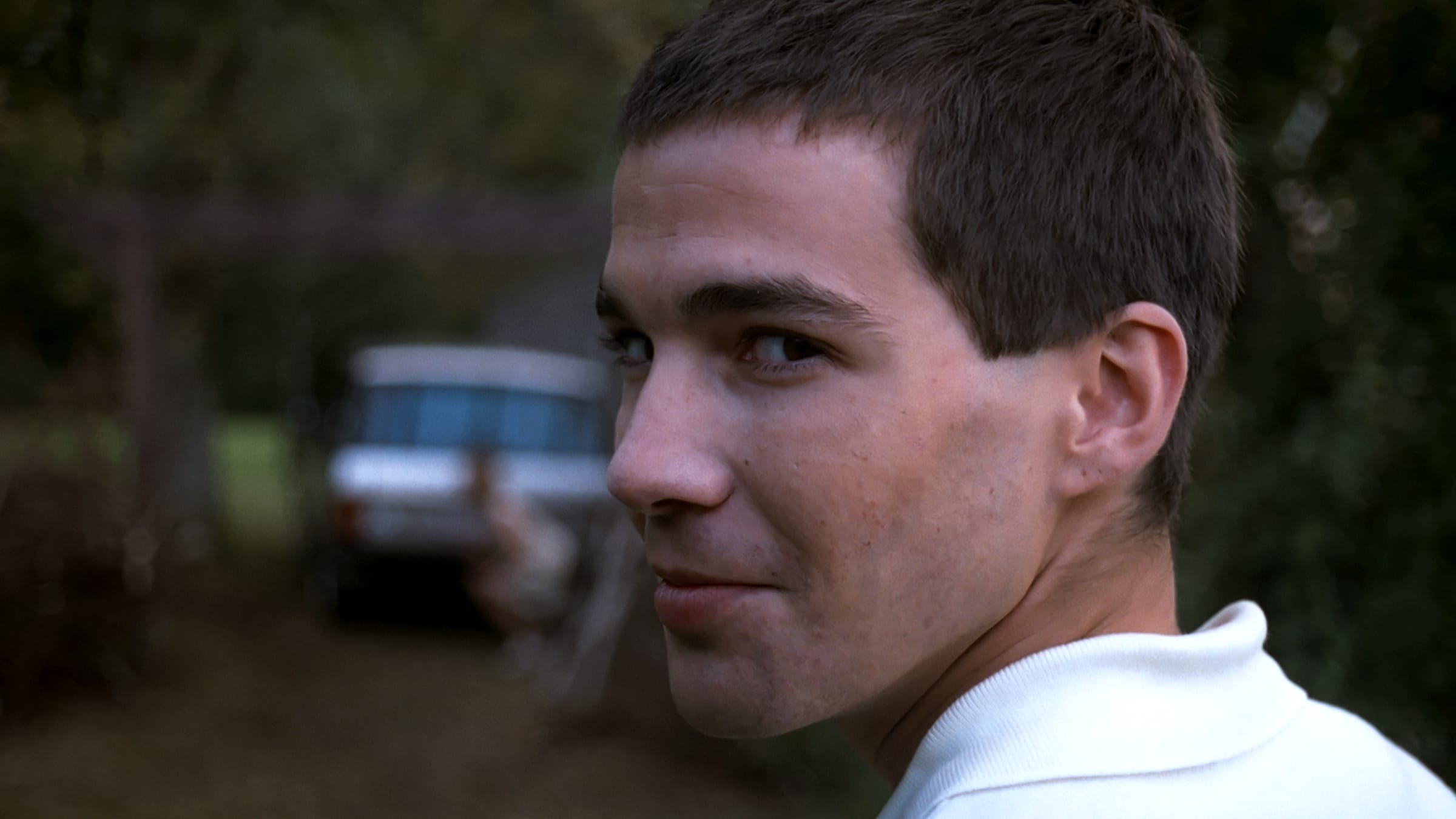

Funny Games follows the upper-class family of Anna (Susanne Lothar), George (Ulrich Mühe), son Georgie (Stefan Clapczynski), and dog Rolfi (Rolfi?), who arrive at their lake house for a few weeks of undisturbed peace. Soon after their arrival, they’re met by Paul (Arno Frisch) and Peter (Frank Giering), two white-clad yuppies who seem just a bit off. Who will survive and who will die in this game that is less funny than the title suggests?

I’ve made this statement about Scream time and time again. Before I get into it too much, let’s take a quick step back to ward off the Ryan C. Showers-like people. I love Scream (as well as 2, 5, and 6). It created a new wave of filmmakers and singlehandedly brought the slasher subgenre back from the dead like a Resident Evil zombie. Like what Tarantino did to independent crime thrillers of the 2000s and 10s, Scream has done to slashers. Post-Scream, slashers felt the need to be overtly meta and as twisty as possible, even at the film’s own demise. There is nothing wrong with a slasher film attempting to be smart. The problem arises when filmmakers who can’t pull it off think they can.

Is Funny Games Anti-Horror or Anti-Slasher?

The barebones rumblings I’ve heard about Funny Games over the years are that writer/director Michael Haneke calls it anti-horror. I would posit that Funny Games unknowingly found itself as more of an anti-slasher rather than an anti-horror. (Hell, it could be both!) Scream would release to acclaim just one year before Haneke’s incredible creation, so I can’t definitively say that Funny Games is a direct response to Scream, as much as I would like to.

Meta-ness has existed in cinema and art long before Scream came to be. Though if you had asked me when I was a freshman in high school, I would have told you Wes Craven created the idea of being meta. It just strikes me as a bit odd that two incredibly meta horror films would be released just one year apart and have such an impact on the genre. Whereas Scream uses its meta nature to make the audience do the Leonardo in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood… meme, Haneke uses it as a mirror for the audience.

Scream vs. Funny Games: A Clash of Meta Intentions

Scream doesn’t ask the audience to figure out which killer is behind the mask at which points; it just assumes that you will suspend your disbelief enough to accept it. Funny Games subverts this idea by showing you the perpetrators immediately and then forcing you to sit in the same room with them, faces uncovered, for nearly the film’s entire runtime. Scream was flashy and fun, Funny Games is long and uncomfortable. Haneke forces the audience to sit with the atrocities and exist within the trauma felt by the family as they’re brutally picked off one by one.

Funny Games utilizes fourth wall breaks to wink at the audience. Haneke is, more or less, trying to make the audience feel bad for what they’re watching. Each time Paul looks at the camera, it’s almost as if he’s saying, “You wanted this.” One of the most intriguing moments in the film is when Peter gets killed and Paul says, “Where is the remote?” before grabbing it, pressing rewind, and going back moments before Anna kills Peter. This is a direct middle finger to the audience. You think you’re getting a final girl in this nasty picture? Hell no. You asked for this, so you’re getting this.

A Contemptuous Look at Slasher Tropes

Both Funny Games are the only Haneke films I’ve seen, so I can’t speak much on his oeuvre. But Funny Games almost feels contemptful about horror, slashers in particular. The direct nature of the boys and their constant presence in each scene eliminates any potential plot holes. E.g., how did Jason Voorhees get from one side of the lake to a cabin a quarter of a mile away? You just have to believe! In horror, we’ve come to accept that when you’re watching a slasher film, you MUST accept what’s given to you. Haneke proves it can be done simply and effectively.

Whether you think it’s horror or not, Funny Games is one of the greatest horror films of all time. Before the elevated horror craze that exists to inflict misery on the viewers, Haneke had “been there, done that.” When [spoiler] dies, [spoiler] and [spoiler] sit in the living room in silence for nearly two minutes in a single uncut shot. Then, in the same uncut shot, [spoiler] starts keening for another two or three minutes. Nearly every slasher film moves on after a kill. Occasionally, we’ll get a funeral service or a memorial set up at the local high school for the slain teenagers. But there’s rarely an effective reflection on the loss of life in a slasher film. Funny Games tells you that you will reflect on death because you asked for death. You bought the ticket (rented the film), so you must reap what you sow.

Why Funny Games Remains One-of-a-Kind

This piece has been overly harsh on slasher films, and that was not the intention. Behind found footage, slasher films are probably my second favorite subgenre. As someone who has watched their fair share of them, it’s easy to see the pre-Scream and post-Scream shift. But there’s this weird disconnect where slasher films had transformed from commentary on life and loss to nothing more than flashy kills where a clown saws a woman from crotch to cranium, and then refuses to pay her fairly. Funny Games is an impressive meditation on horror and horror audiences. Even the title is a poke at the absurdity of slashers. If you haven’t seen Funny Games, I highly suggest checking it out because I can promise you, you’ve never seen a horror film like it. And we probably never will again.

Editorials

‘The Woman in Black’ Remake Is Better Than The Original

As a horror fan, I tend to think about remakes a lot. Not why they are made, necessarily. That answer is pretty clear: money. But something closer to “if they have to be made, how can they be made well?” It’s rare to find a remake that is generally considered to be better than the original. However, there are plenty that have been deemed to be valuable in a different way. You can find these in basically all subgenres. Sci-fi, for instance (The Thing, The Blob). Zombies (Dawn of the Dead, Evil Dead). Even slashers (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, My Bloody Valentine). However, when it comes to haunted house remakes, only The Woman in Black truly stands out, and it is shockingly underrated. Even more intriguingly, it is demonstrably better than the original movie.

The Original Haunted House Movie Is Almost Always Better

Now please note, I’m specifically talking about movies with haunted houses, rather than ghost movies in general. We wouldn’t want to be bringing The Ring into this conversation. That’s not fair to anyone.

Plenty of haunted house movies are minted classics, and as such, the subgenre has gotten its fair share of remakes. These are, almost unilaterally, some of the most-panned movies in a format that attracts bad reviews like honey attracts flies.

You’ve got 2005’s The Amityville Horror (a CGI-heavy slog briefly buoyed by a shirtless, possessed Ryan Reynolds). That same year’s Dark Water (one of many inert remakes of Asian horror films to come from that era). 1999’s The House on Haunted Hill (a manic, incoherent effort that millennial nostalgia has perhaps been too kind to). That same year there was The Haunting (a manic, incoherent effort that didn’t even earn nostalgia in the first place). And 2015’s Poltergeist (Remember this movie? Don’t you wish you didn’t?). And while I could accept arguments about 2001’s THIR13EN Ghosts, it’s hard to compete with a William Castle classic.

The Problem with Haunted House Remakes

Generally, I think haunted house remakes fail so often because of remakes’ compulsive obsession with updating the material. They throw in state-of-the-art special effects, the hottest stars of the era, and big set piece action sequences. Like, did House on Haunted Hill need to open with that weird roller coaster scene? Of course it didn’t.

However, when it comes to haunted house movies, bigger does not always mean better. They tend to be at their best when they are about ordinary people experiencing heightened versions of normal domestic fears. Bumps in the night, unexplained shadows, and the like. Maybe even some glowing eyes or a floating child. That’s all fine and dandy. But once you have a giant stone lion decapitating Owen Wilson, things have perhaps gone a bit off the rails.

The One Big Exception is The Woman in Black

The one undeniable exception to the haunted house remake rule is 2012’s The Woman in Black. If we want to split hairs, it’s technically the second adaptation of the Susan Hill novel of the same name. But The Haunting was technically a Shirley Jackson re-adaptation, and that still counts as a remake, so this does too.

The novel follows a young solicitor being haunted when handling a client’s estate at the secluded Eel Marsh House. The property was first adapted into a 1989 TV movie starring Adrian Rawlings, and it was ripe for a remake. In spite of having at least one majorly eerie scene, the 1989 movie is in fact too simple and small-scale. It is too invested in the humdrum realities of country life to have much time to be scary. Plus, it boasts a small screen budget and a distinctly “British television” sense of production design. Eel Marsh basically looks like any old English house, with whitewashed walls and a bland exterior.

Therefore, the “bigger is better” mentality of horror remakes took The Woman in Black to the exact level it needed.

The Woman in Black 2012 Makes Some Great Choices

2012’s The Woman in Black deserves an enormous amount of credit for carrying the remake mantle superbly well. By following a more sedate original, it reaches the exact pitch it needs in order to craft a perfect haunted house story. Most appropriately, the design of Eel Marsh House and its environs are gloriously excessive. While they don’t stretch the bounds of reality into sheer impossibility, they completely turn the original movie on its head.

Eel Marsh is now, as it should be, a decaying, rambling pile where every corner might hide deadly secrets. It’d be scary even if there wasn’t a ghost inside it, if only because it might contain copious black mold. Then you add the marshy grounds choked in horror movie fog. And then there’s the winding, muddy road that gets lost in the tide and feels downright purgatorial. Finally, you have a proper damn setting for a haunted house movie that plumbs the wicked secrets of the wealthy.

Why The Woman in Black Remake Is an Underrated Horror Gem

While 2012’s The Woman in Black is certainly underrated as a remake, I think it is even more underrated as a haunted house movie. For one thing, it is one of the best examples of the pre-Conjuring jump-scare horror movie done right. And if you’ve read my work for any amount of time, you know how positively I feel about jump scares. The Woman in Black offers a delectable combo platter of shocks designed to keep you on your toes. For example, there are plenty of patient shots that wait for you to notice the creepy thing in the background. But there are also a number of short sharp shocks that remain tremendously effective.

That is not to say that the movie is perfect. They did slightly overstep with their “bigger is better” move to cast Daniel Radcliffe in the lead role. It was a big swing making his first post-Potter role that of a single father with a four-year-old kid. It’s a bit much to have asked 2012 audiences to swallow, though it reads slightly better so many years later.

However, despite its flaws, The Woman in Black remake is demonstrably better than the original. In nearly every conceivable way. It’s pure Hammer Films confection, as opposed to a television drama without an ounce of oomph.