Editorials

‘Donnie Darko’: A Critique of Conservatism and Book Bans in Schools

Let’s be honest with ourselves. On your first watch, second, fifteenth, did you ever figure out what the cult classic Donnie Darko is about? I will confess. I had absolutely no idea what Donnie Darko was about. And I still don’t. Not quite.

A Poignant Look at the Current School Systems

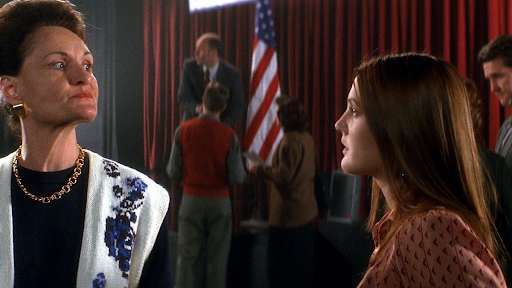

But the film’s warnings of pervasive and predatory conservatism facilitate important conversations surrounding censorship in the American post-Trump era, and illuminate just how out of touch the powers that be are with the needs of the younger generations. The central antagonist of Donnie Darko is not the giant bunny, not the bullies, but the conservative parent/gym teacher Kitty Farmer, whose lack of understanding of Middlesex’s youth causes extreme tension in the town. Farmer’s call for a book ban of Graham Greene’s “The Destructors,” given as a reading assignment by Miss Karen Pomeroy. Her reasons behind the ban enlighten us to what is currently happening in schools across the United States, especially in the South. The film’s post-Reagan political climate further enriches the comparisons to today’s post-Trump world, and politics is no doubt an ominous specter throughout the film.

Political Tensions in Donnie Darko

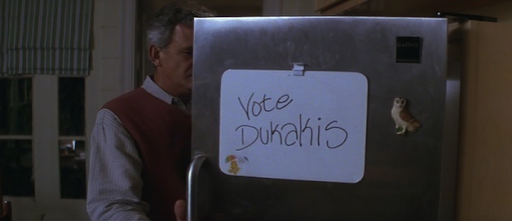

Donnie Darko is set in Middlesex, Virginia, in 1988. It is October, and the 1988 election is near. The film’s first piece of dialogue comes from Donnie’s sister Elizabeth at the family dinner table. “I’m voting for Dukakis,” she confesses to her parents. Mr. Darko pauses mid-bite, shocked. “Hmm, well. Maybe when you have children of your own who need braces, and you can’t afford them because half of your husband’s paycheck goes to the federal government, who umm…” “—my husband’s paycheck?” she interrupts. Mrs. Darko affirms her daughter with a giggle. However, she soon chides in, asking Elizabeth if she really thinks Dukakis, the Democratic nominee, will “provide for this country” until she’s ready to have children.

By now, we have learned that Elizabeth is eagerly awaiting an acceptance from Harvard University. This first scene sets the film’s political tone: conservative values reign and are in direct opposition to a bright young generation. Donnie Darko showcases the generation gap between the Baby Boomers and Generation X. Considering our political climate after just having an ultra-conservative showman president just as Donnie Darko is set amidst the race to succeed Ronald Reagan. The film is a window into the effects of the Moral Majority/GOP on schools, teachers, parents, and children. And sadly, the results are what you’d expect: conservative opposition to intellectualism/higher education, and an over-policing of children and teens. Sound familiar?

At Middlesex High School, English teacher Miss Karen Pomeroy introduced her students to the story “The Destructors.” This is a tale of a gang of child ruffians in the ruins of London in World War II after The Blitz. Together, they flood and dismantle the house of ‘Old Misery,’ a man whose house, unlike his neighbors’, survived The Blitz completely. The story includes a moment when the leader, T, finds bundles of cash in Old Misery’s mattress and instead of stealing it, he lights it aflame. When Miss Pomeroy asks what this scene in the story means, Donnie explains, “They just wanna see what happens when they tear the world apart. They want to change things.”

Kitty Farmer’s Crusade Against Literature

“The PTA doesn’t ban books.”

Unfortunately, the assignment from Miss Pomeroy was also given to Beth Farmer, Kitty Farmer’s daughter. An enraged Mrs. Farmer disrupts an Emergency PTA meeting to advocate for a school book ban. “I want to know why this smut is being taught to our children!” The PTA was on the topic of recent school vandalism, which included a flooding of the school (Frank, Donnie’s imaginary friend, instructed Donnie to do this). She cites that the child gang in “The Destructors” used flooding in their mission for destruction, which is what happened to the school earlier that month. Farmer receives scattered cheers from the parents present, but not from Rose Darko. “What is the real issue here?” she asks Kitty. “The PTA doesn’t ban books.”

Farmer continues, “The PTA is here to acknowledge that pornography is being taught in our curriculum!”

The Mislabeling of Literature as “Pornography”

According to Pen America, a literature and human rights organization, it is quite common for books to be labeled “pornographic” or “indecent.” However, as in Greene’s story, it is often the case that the books being accused of sexual content contain nothing of the sort.

[T]his framing has become an increasing focus of activists and politicians to justify removing books that do not remotely fit the well-established legal and colloquial definitions of “pornography.” Rhetoric about ‘porn in schools’ has also been advanced as justification for the passage or introduction of new state laws, some of which would bar any books with sexual content and could easily sweep up a wide swath of literature and health-related content.

Conspiracies and Hypocrisy in Donnie Darko

When Karen Pomeroy explains that the story is ironic, Kitty hurls with vitriol, “[Y]ou need to go back to grad school.” Kitty prefers her limited understanding to an intellectual conversation about the literature. Just as it is happening today, conscientious and knowledgeable teachers are being policed and scrutinized for routine classroom decisions on curriculum, while those who critique their actions follow abusive demigods with no question of their morals. It is later revealed that Kitty Farmer’s idol, motivational speaker Jim Cunningham, is a serial child predator who she introduced to children and adults in Middlesex. Kitty misses her daughter’s big break in Hollywood to be at his side for the trial. “It’s obviously some kind of conspiracy to destroy an innocent man!”

Though Farmer had no problem destroying Miss Pomeroy’s career. Within a few weeks of introducing Greene’s story to her class, Miss Pomeroy is fired after Farmer’s complaints with support from the school principal. She tells him, “I don’t think that you have a clue what it’s like to communicate with these kids. And we are losing them to apathy… to this prescribed nonsense.” Similarly, an Oklahoma teacher in 2022 was fired for providing students with access to banned books. Folks like Kitty Farmer, of which there are many, want to “protect children” by banning controversial literature while they are the real predators.

Donnie Darko and the Myth of Literary Influence

To Kitty’s point, could Donnie have been directly inspired by “The Destructors,” causing chaos in Middlesex? The answer is no. Donnie Darko deals with fate, and Donnie was always on this path, as posited by the film’s central premise of time travel. In this sense, the film can be a vehicle to analyze conservative hysteria toward literature — children will always find a way to rebel, and perhaps in defiance, be inspired by the actions of conservatives to call for an end to book bans and censorship in schools.

Donnie was certainly inspired by his distaste for hypocritical and conservative school leadership. Even though his actions, or at least what his imaginary friend Frank told him to do, mirror those in the story, “The Destructors” did not dictate his behavior. Even further, the gang of boys did not kill anyone, unlike Donnie. He tells Gretchen early in the film that he had burned down an abandoned house once before, prior to his introduction to Greene’s story. Destruction/creation is Donnie’s destiny.

Honoring Teachers Like Miss Pomeroy

I and many others have had our own Miss Pomeroys, the bright English teachers who, despite colleague scrutiny or petty gossip introduced kids to texts we may have only found with their help. Morrison, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Ginsberg, and countless other luminaries were sent my and other students’ way. But then again, I went to a public high school in New York. Teachers and students in conservative areas are facing the wrath of their own Kitty Farmers, many of whom have already infiltrated their schools, towns, and state legislatures.

These are scary times. To the Miss Pomeroys across the United States, thank you and keep going.

Editorials

The 10 Most Satisfying Deaths in Horror Movies

Horror Press’ exploration of catharsis this month lends itself naturally to the topic of satisfying horror movie deaths. While murdering people who vex you in real life is rightly frowned upon, horror allows us to explore our darker sides. Fiction gives us the catharsis and relief to allow us to survive that ineradicable pox that is other people. To that end, here are the 10 most satisfying deaths in horror movies.

PS: It goes without saying that this article contains a few SPOILERS.

The 10 Most Satisfying Deaths in Horror Movies

#10 Franklin, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

I ranked this death from the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre lowest for two reasons. First, I think Franklin’s whole vibe is a perfect fit for the unnerving, overwhelming atmosphere of Tobe Hooper’s masterpiece. Second, I think it’s important for representation that onscreen characters from marginalized groups be allowed to have flaws. That said, Franklin Hardesty is one of the most goddamn annoying characters in the history of cinema. Endless shrieking and raspberry-blowing will do that for ya. His death via chainsaw comes as a profound relief. His sister Sally spends the next 40 minutes or so screaming nonstop, and that’s considerably more peaceful.

#9 Lori, Happy Death Day

This is less about the character herself and more about Tree’s journey. After watching her time-loop for so long, being thwarted at every turn, Lori’s poison cupcake is a real gut-punch. Tree’s vengeance allows her to break out of the time loop once and for all (until the sequel). It also allows us to rejoice in the fact that her work to improve herself hasn’t been for naught.

#8 Billy, Scream (1996)

There are a hell of a lot of satisfying kills perpetrated upon Ghostfaces in the Scream franchise. However, the original still takes the cake. Sidney Prescott curtly refuses to allow a killer to plug a sequel at the end of her survival story. Instead, she plugs him in the head, saying, “Not in my movie.” It’s not just a great ending to a horror movie. It’s a big middle finger to sleazy teenage boyfriends the world over.

#7 Crispian, You’re Next

Ooh, when Erin finds out that this rotten man has knowingly brought her along to a home invasion… His attempt to charm (and bribe) her might have won over a weaker person. But in addition to putting her in danger, he has willingly had his family slaughtered for money. Erin won’t stand for that, and her takedown of yet another Toxic Horror Boyfriend is cause for celebration.

#6 Charles, Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan

Charles McCulloch might be one of the nastiest characters in film history. While school administrators are hardly any student’s best friend, his cold cruelty is downright abnormal. How he manages to be simultaneously overbearing and wicked to his niece, Rennie, I’ll never know. But thankfully, Jason Voorhees drowns him in a vat of toxic waste, removing the need to solve that mystery. Not all heroes wear capes. Sometimes they wear hockey masks.

#5 Tyler, The Menu

Up next on the tasting tray of cinema’s worst boyfriends, we have Tyler. He’s not technically Margot’s boyfriend, because she’s an escort he invited to a fancy dinner. But he should still land in the hall of fame. That’s because he brought her despite knowing ahead of time that nobody was meant to leave the restaurant alive. Thankfully, he gets one of the best Bad Boyfriend deaths of them all. He dies at his own hands. By hanging. After being thoroughly humiliated with proof that all the mansplaining in the world can’t make someone a good chef. Delectable.

#4 The Baby, Immaculate

You may remember this kill from my Top 10 Child Deaths article. The ending of Immaculate is (there’s no other word for it) immaculate. Shortly after Sister Cecilia learns that she has been unwillingly impregnated with the son of Christ, she gives birth. Instead of letting the church manipulate her further after violating her body, she smashes that godforsaken thing with a rock. In the process, she sheds years of ingrained doctrine and sets herself free once and for all. This is the ending that Antichrist movies have historically been too cowardly to give us. The fact that this character is a potential messiah makes it that much more cathartic.

#3 Carter, The Final Destination

I mean, come on. This guy is literally credited as “Racist” at the end of the movie. Pretty much every Final Destination movie has an asshole character who you crave to see die. But this epithet-spewing, cross-burning bigot is by far the worst of the bunch.

#2 Dean, Get Out

Racism comes in many forms, as Jordan Peele’s Get Out highlights. The Armitage family’s microaggressions quickly become macroaggressions, more than justifying Chris’ revenge slayings. While this whole portion of the movie is immensely satisfying, Dean’s death might just be the most cathartic. This is because he is killed via the antlers of a stuffed deer head. Chris uses the family’s penchant for laying claim to their prey’s bodies against them with this perfectly violent metaphor.

#1 Adrian, The Invisible Man (2020)

Here we have the final boss of Toxic Horror Boyfriends. This man is so heinously abusive that he fakes his own death in order to torment his ex even more. Cee using his own invisibility suit against him to stage his death by suicide is perfectly fitting revenge.

Editorials

‘Ready or Not’ and the Cathartic Cigarette of a Relatable Final Girl

I was late to the Radio Silence party. However, I do not let that stop me from being one of the loudest people at the function now. I randomly decided to see Ready or Not in theaters one afternoon in 2019 and walked out a better person for it. The movie introduced me to the work of a team that would become some of my favorite current filmmakers. It also confirmed that getting married is the worst thing one can do. That felt very validating as someone who doesn’t buy into the needing to be married to be complete narrative.

Ready or Not is about a fucked up family with a fucked up tradition. The unassuming Grace (Samara Weaving) thinks her new in-laws are a bit weird. However, she’s blinded by love on her wedding day. She would never suspect that her groom, Alex (Mark O’Brien), would lead her into a deadly wedding night. So, she heads downstairs to play a game with the family, not knowing that they will be hunting her this evening. This is one of the many ways I am different from Grace. I watch enough of the news to know the husband should be the prime suspect, and I have been around long enough to know men are the worst. I also have a commitment phobia, so the idea of walking down the aisle gives me anxiety.

Grace Under Fire

Ready or Not is a horror comedy set on a wealthy family’s estate that got overshadowed by Knives Out. I have gone on record multiple times saying it’s the better movie. Sadly, because it has fewer actors who are household names, people are not ready to have that conversation. However, I’m taking up space this month to talk about catharsis, so let me get back on track. One of the many ways this movie is better than the latter is because of that sweet catharsis awaiting us at the end.

This movie puts Grace through it and then some. Weaving easily makes her one of the easiest final girls to root for over a decade too. From finding out the man she loves has betrayed her, to having to fight off the in-laws trying to kill her, as she is suddenly forced to fight to survive her wedding night. No one can say that Grace doesn’t earn that cigarette at the end of the film. As she sits on the stairs covered in the blood of what was supposed to be her new family, she is a relatable icon. As the unseen cop asks what happened to her, she simply says, “In-laws.” It’s a quick laugh before the credits roll, and “Love Me Tender” by Stereo Jane makes us dance and giggle in our seats.

Ready or Not Proves That Maybe She’s Better Off Alone

It is also a moment in which Grace is one of many women who survives marriage. She comes out of the other side beaten but not broken. Grace finally put herself, and her needs first, and can breathe again in a way she hasn’t since saying I do. She fought kids, her parents-in-law, and even her husband to escape with her life. She refused to be a victim, and with that cigarette, she is finally free and safe. Grace is back to being single, and that’s clearly for the best.

This Guy Busick and R. Christopher Murphy script is funny on the surface, even before you start digging into the subtext. The fact that Ready or Not is a movie where the happy ending is a woman being left alone is not wasted on me, though. While Grace thought being married would make her happy, she now has physical and emotional wounds to remind her that it’s okay to be alone.

One of the things I love about this current era of Radio Silence films is that the women in these projects are not the perfect victims. Whether it’s Ready or Not, Abigail, or Scream (2022), or Scream VI, the girls are fighting. They want to live, they are smart and resourceful, and they know that no one is coming to help them. That’s why I get excited whenever I see Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett’s names appear next to a Guy Busick co-written script. Those three have cracked the code to give us women protagonists that are badasses, and often more dangerous than their would-be killers when push comes to shove.

Ready or Not Proves That Commitment is Scarier Than Death

So, watching Grace run around this creepy family’s estate in her wedding dress is a vision. It’s also very much the opposite of what we expect when we see a bride. Wedding days are supposed to be champagne, friends, family, and trying to buy into the societal notion that being married is what we’re supposed to aspire to as AFABs. They start programming us pretty early that we have to learn to cook to feed future husbands and children.

The traditions of being given away by our fathers, and taking our husbands’ last name, are outdated patriarchal nonsense. Let’s not even get started on how some guys still ask for a woman’s father’s permission to propose. These practices tell us that we are not real people so much as pawns men pass off to each other. These are things that cause me to hyperventilate a little when people try to talk to me about settling down.

Marriage Ain’t For Everybody

I have a lot of beef with marriage propaganda. That’s why Ready or Not speaks to me on a bunch of levels that I find surprising and fresh. Most movies would have forced Grace and Alex to make up at the end to continue selling the idea that heterosexual romance is always the answer. Even in horror, the concept that “love will save the day” is shoved at us (glares at The Conjuring Universe). So, it’s cool to see a movie that understands women can be enough on their own. We don’t need a man to complete us, and most of the time, men do lead to more problems. While I am no longer a part-time smoker, I find myself inhaling and exhaling as Grace takes that puff at the end of the film. As a woman who loves being alone, it’s awesome to be seen this way.

The Cigarette of Singledom

We don’t need movies to validate our life choices. However, it’s nice to be acknowledged every so often. If for no other reason than to break up the routine. I’m so tired of seeing movies that feel like a guy and a girl making it work, no matter the odds, is admirable. Sometimes people are better when they separate, and sometimes divorce saves lives. So, I salute Grace and her cathartic cigarette at the end of her bloody ordeal.

I cannot wait to see what single shenanigans she gets into in Ready or Not 2: Here I Come. I personally hope she inherited that money from the dead in-laws who tried her. She deserves to live her best single girl life on a beach somewhere. Grace’s marriage was a short one, but she learned a lot. She survived it, came out the other side stronger, richer, and knowing that marriage isn’t for everybody.