Editorials

Examining the Nuclear Family in ‘The Hills Have Eyes’ (2006)

What is it about The Hills Have Eyes (2006) that’s so appealing? And what makes it “a perfect remake” in my eyes? 2006 was not a great time in America; even a foreign filmmaker could see that. America thrust itself into a false war for oil, under the guise of fighting terrorism, and the housing market was on the verge of its collapse. The Hills Have Eyes, and many of the reboots of this time took that anger many people felt and funneled that into the antagonists of some of our most beloved franchises. The antagonists in the original film were unquestionably bad people, but it’s the family in the reboot that feels even crueler and bloodthirsty. You see this in Michael Bay’s Texas Chainsaw, with Leatherface somehow being crueler and ominous. Hell, even Rob Zombie’s Michael Myers is a hulking, terrifying creature, much more than Carpenter’s original (don’t kill me). Seeing good ultimately besting this seemingly unbeatable evil brought a level of hope to some people who felt they had no other escape. Beauty dies at the beginning of the film and by the time Doug walks out of the canyon with Catherine in his arms, he’s guided out by Beast. I think the anger felt in the films of this time spoke with a world that was full of so much of it.

When you think of mid-aughts remakes or reboots what comes to mind? Halloween? The Texas Chainsaw Massacre? House of Wax? When I’m asked about remakes, one film always comes to mind immediately: The Hills Have Eyes. Critically mixed and financially successful, The Hills Have Eyes fell into the laps of horror fans amidst a barrage of remakes and reboots throughout the mid-aughts. Films like The Ring and The Grudge had proven remakes could be insanely financially successful, especially during October. What’s really interesting about the trend of mid-aughts remakes is how it didn’t start in the 2000s. Instead, it began in the year 1999.

In a move that would be copied by Michael Bay just a few years later, Academy Award Winner Robert Zemeckis and Joel Silver created Dark Castle Entertainment. Dark Castle’s goal was to remake the films of genre icon William Castle. Little did they know they would start a trend to define an entire decade of horror. The first film from Dark Castle was House on Haunted Hill. The incredibly frightening remake would shoot to the number one spot at the box office upon its October release, grossing $15,946,032 in its opening weekend, setting a financial precedent on the validity of a new wave of remakes. Just three years later The Ring would not be able to beat Haunted Hill, with its $15,015,393 opening weekend. However, we can’t forget The Ring grossed a worldwide total of $249,348,933.

A String of Remakes Brings Us to The Hills

One year later, Michael Bay’s studio Platinum Dunes would try its hand at genre remakes with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. This was when people realized remakes could be financially successful on IP alone as TCM made a whopping $10 million on opening day and a jaw-dropping $29 million on its opening weekend, despite overwhelmingly negative reviews. Finally, the fuel that catalyzed the aught’s remakes came from The Grudge. The Grudge had an opening weekend of $39,128,715, with a worldwide gross of $187 million! The rest of the 2000s would see the remakes of films like The Amityville Horror, Halloween, House of Wax, and A Nightmare on Elm Street.

Cut to 2006. Upon hearing of the financial success of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Amityville Horror, Wes Craven had an itch to bring one of his properties back. Instead of resurrecting his most successful franchise, A Nightmare on Elm Street, he decided his cult-favorite The Hills Have Eyes would be the perfect film to reboot. The 1977 release of The Hills Have Eyes was indeed a financial success, despite what producer Peter Locke would like to think. By October 1977, the film had made around $2 million, adjusted to almost $10 million today, on its budget of $350k to $700k. By the end of its theatrical run, it would make an incredible $25 million, adjusted for over $100 million. Okay, no more money talk. But that’s pretty impressive, no?

Alexandre Aja and the New French Extremity Influence

Wes Craven’s producing partner Marianne Maddalena introduced him to the New French Extremity film High Tension. Craven was impressed. After a meeting with Alexandre Aja, and his collaborator Grégory Levasseur, Wes Craven knew who would reboot his bloody desert story. Receiving mixed reviews, The Hills Have Eyes opened at third in the box office in March. Its run at the box office would gross 70 million dollars, absolutely eclipsing its $15 million dollar budget. And that is the story of what I would describe as, how the perfect reboot came to be. But what is it about this film that I, and many fans, love so much?

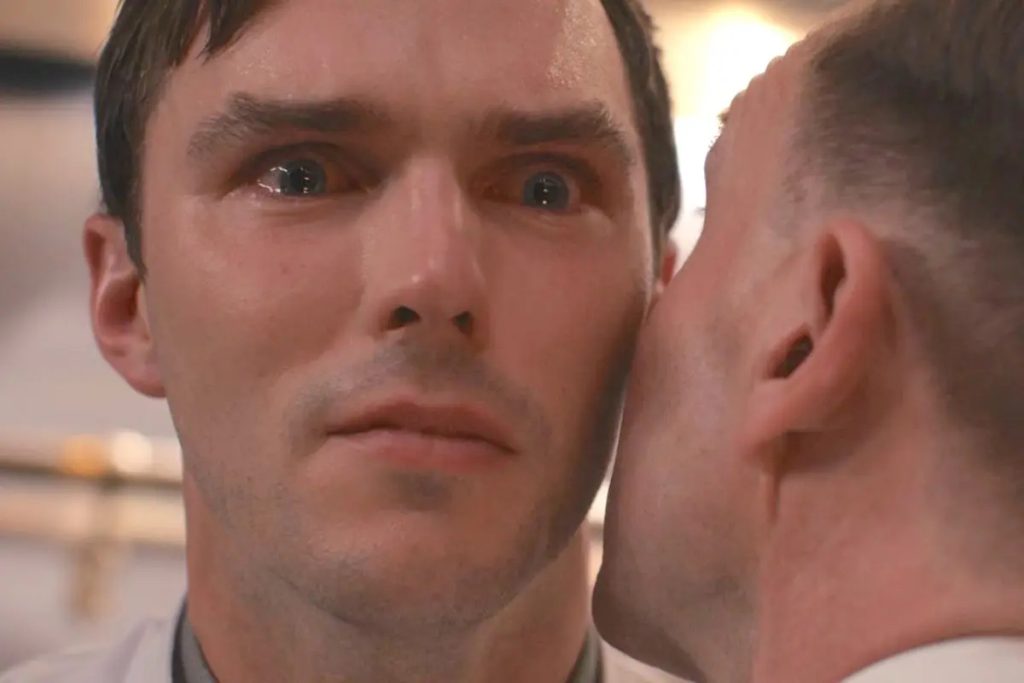

The Hills Have Eyes follows a family, well technically two families, on a road trip for their parent’s anniversary. We have Big Bob Carter (Ted Levine), his wife Ethel (Kathleen Quinlan), his daughters Brenda (Emilie de Ravin) and Lynn Carter-Bukowski (Vinessa Shaw), his son Bobby (Dan Byrd), Lynn’s husband Doug (Aaron Stanford), and Lynn and Doug’s baby Catherine (Maisie Camilleri Preziosi). After an accident with their car and camper, they find themselves stuck in the desert. Only they are not alone. In the hills, and over the ridge, reside a family of cannibal mutants led by Papa Jupiter (Billy Drago) and his children Lizard (Robert Joy), Big Brain (Desmond Askew), Goggle (Ezra Buzzington), Pluto (Michael Bailey Smith), Ruby (Laura Ortiz), Big Mama (Ivana Turchetto), Cyst (Greg Nicotero), Venus (Judith Jane Vallette), and Mercury (Adam Perrell).

Social Commentary in The Hills Have Eyes Remake

The original and the remake offer a few pieces of commentary, one being a hellish rebuke of class warfare, the haves and the have-nots. Where the remake becomes a lot more interesting than the original is who wrote and directed it. Having Alexandre Aja and Grégory Levasseur on board for a film like this is almost the perfect match. They are no stranger to ultra-violence and political commentary. Stepping out of the shadow of their film about repressed sexuality and mental health, Aja and Lavasseur tell a tale that feels deeply American, even if the filmmakers are French. The script holds a mirror up to us and shows how much of the world sees Americans and how we treat the less fortunate. It’s even more true now than ever. Within a one-block vicinity of Penn Station, you’ll find a plethora of unhoused people the system has seemingly given up on. They’re demonized for the position they’re put in due to countless governmental failings and lack of genuine assistance.

The antagonists in The Hills Have Eyes find themselves forgotten by the world after a set of nuclear tests scourged their homes. What was once a thriving mining town is now a barren wasteland of a forgotten time. Now yes, they are cannibals and killers, but one can’t help but understand their ends are caused by the means. Like the original film, they’re not just cannibals, as The Carters’s dog Beauty is eaten in both films. The cannibal family has most likely hunted their respective land to near extinction, especially due to the size of some of the sons; they’re massive!

Creature Design: Inspired by Real-Life Tragedies

Cannibalism aside, the family looks quite gnarly. KNB EFX handled the arduous 6-month creature design process. However, it goes to show how much passion Aja and Lavasseur had as they had already visually conceived the creatures quite thoroughly. Their inspirations for the designs were based on real-life documentation of the fallout from places like Chernobyl and Hiroshima. Papa Jupiter and Big Mama are presumably the heads of the family. They don’t have any deformities, so we can assume their spawn were either hit from a very young age with large doses of radiation that affected their growth or the radiation received by Papa Jupiter and Big Mama affected their reproductive systems in a way that created their deformities. Part of me wants to believe that while Papa and Mama are the ring leaders, Big Brain is the logistics guy.

We do see humanity within the cannibal family from Ruby. What is Ruby’s role? Initially, we are introduced to Jeb (Tom Bower), the gas station owner. Ruby is seen bringing him a bag of goodies taken from previous victims. Jeb tells Ruby he’s out, and Ruby, who finds herself at the same crossroads, realizes there’s possibly a way out for her. When Bobby gets knocked out, Ruby makes sure he is safe from Goggle. After Catherine is kidnapped, Doug goes on a death mission to get her back at any cost. Thankfully, Ruby double kidnaps Catherine and tries whisking her away to safety; ultimately causing her brother’s death. The character of Ruby is written incredibly as a tragic antagonist. Thrust into a world of hate and violence, Ruby must overcome a life she’s always known to find her own true happiness. Ruby didn’t ask for this, and she’s determined to end this bloody charade one way or another.

Brutal Additions to the Original The Hills Have Eyes

Most of the remake follows closely to the original story. Still, there are a few grand additions that show just how ruthless the cannibal family is. Papa Jupiter takes advantage of an incredibly intoxicated Jeb, goading into blowing his head off with a shotgun. They also bring back Big Bob’s immolation. But the updated version of the fight between Pluto and Doug is probably the most memorable scene in the film. Their fight spans multiple rooms where Pluto has the upper hand most of the time. Pluto reveals either partial analgesia or a very low pain threshold when Doug stabs him in the stomach with a broken bat, it’s one heck of a stab. At some point later in the fight, Doug stabs Pluto in the foot with a screwdriver, and Pluto reacts in pain. The National Library of Medicine states, “Mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channels SCN9A and SCN11A can cause congenital painlessness.” So it’s not too far off to think some of the cannibals could have lessened pain receptors. Doug eventually bests Pluto in their fight, symbolically, piercing Pluto’s throat with a miniature American flag, and finishing him off with an axe to the head.

Pluto may be the most physically intimidating family member, but Lizard seems to be the most vile family member from what we see. Earlier it was mentioned that Jeb would get rewarded with goodies from victims. That’s because he provided them. Jeb sends The Carters down the “shortcut” because he felt he was being made fun of. Once they’re a significant distance away from the gas station, Lizard uses his spike strip whip to pop the tires on the truck. Later in the camper, when Big Bob is on fire Lizard bites the head off of one of The Carters’s birds, drinks its blood, then rapes Brenda. There’s finally some comeuppance for Lizard during a fight with Doug, when Ruby runs and tackles him off the cliff, killing both of them. This gives Ruby her chance to do something good and thin out the family’s numbers even further. By the film’s end, the only cannibal family members we know are still alive are Big Mama and the two children, Venus and Mercury, as Beast kills Big Brain earlier.

Cinematography and Visual Craftsmanship

Grégory Levasseur would not be the only person from High Tension to join Alexandre Aja on this project, they would also bring along cinematographer Maxime Alexandre. Frequent collaboration between brilliant minds yields the best results. Minute details do wonders to visually set The Hills Have Eyes apart from other films of the time. Messing with frame rates wasn’t new by any means, and films like The Ring and The Grudge even played around with them a bit. But it’s how the image was meticulously crafted in each scene, and whatever frame rate fit that exact emotion was used. Like when Doug enters the town, the frame rate is turned way up to give us a constant feeling of anxiety and pressure, only to then be brought back down, and immediately raised again for the Pluto fight. It’s small and easily overlooked, but it adds so much to the tone.

Why The Hills Have Eyes (2006) Is the Perfect Remake

What is it about The Hills Have Eyes (2006) that’s so appealing? And what makes it “a perfect remake” in my eyes? 2006 was not a great time in America; even a foreign filmmaker could see that. America thrust itself into a false war for oil, under the guise of fighting terrorism, and the housing market was on the verge of its collapse. The Hills Have Eyes, and many of the reboots of this time took that anger many people felt and funneled that into the antagonists of some of our most beloved franchises. The antagonists in the original film were unquestionably bad people, but it’s the family in the reboot that feels even crueler and bloodthirsty.

You see this in Michael Bay’s Texas Chainsaw, with Leatherface somehow being crueler and ominous. Hell, even Rob Zombie’s Michael Myers is a hulking, terrifying creature, much more than Carpenter’s original (don’t kill me). Seeing good ultimately besting this seemingly unbeatable evil brought a level of hope to some people who felt they had no other escape. Beauty dies at the beginning of the film and by the time Doug walks out of the canyon with Catherine in his arms, he’s guided out by Beast. I think the anger felt in the films of this time spoke with a world that was full of so much of it.

The Hills Have Eyes Is A Faithful Yet Innovative Reboot

And why do I think this is the perfect reboot? Alexandre Aja and Grégory Levasseur understood the assignment. They recognized what fans loved about the original film and kept the bones while making it their own. The additions to the story do nothing to take away from the core concept that Craven had in mind with his film. The Hills Have Eyes is a politically poignant film that can still be viewed as just a film. There is a message there, but it doesn’t overtake the film in an over-the-top way. When I watch a remake of a film I love, I want to see the aspects of what initially drew me into it, and I want to see the story told in a new way. That is exactly what Alexandre Aja and Grégory Levasseur did.

That can’t be said for The Hills Have Eyes 2.

Editorials

The 10 Most Satisfying Deaths in Horror Movies

Horror Press’ exploration of catharsis this month lends itself naturally to the topic of satisfying horror movie deaths. While murdering people who vex you in real life is rightly frowned upon, horror allows us to explore our darker sides. Fiction gives us the catharsis and relief to allow us to survive that ineradicable pox that is other people. To that end, here are the 10 most satisfying deaths in horror movies.

PS: It goes without saying that this article contains a few SPOILERS.

The 10 Most Satisfying Deaths in Horror Movies

#10 Franklin, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

I ranked this death from the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre lowest for two reasons. First, I think Franklin’s whole vibe is a perfect fit for the unnerving, overwhelming atmosphere of Tobe Hooper’s masterpiece. Second, I think it’s important for representation that onscreen characters from marginalized groups be allowed to have flaws. That said, Franklin Hardesty is one of the most goddamn annoying characters in the history of cinema. Endless shrieking and raspberry-blowing will do that for ya. His death via chainsaw comes as a profound relief. His sister Sally spends the next 40 minutes or so screaming nonstop, and that’s considerably more peaceful.

#9 Lori, Happy Death Day

This is less about the character herself and more about Tree’s journey. After watching her time-loop for so long, being thwarted at every turn, Lori’s poison cupcake is a real gut-punch. Tree’s vengeance allows her to break out of the time loop once and for all (until the sequel). It also allows us to rejoice in the fact that her work to improve herself hasn’t been for naught.

#8 Billy, Scream (1996)

There are a hell of a lot of satisfying kills perpetrated upon Ghostfaces in the Scream franchise. However, the original still takes the cake. Sidney Prescott curtly refuses to allow a killer to plug a sequel at the end of her survival story. Instead, she plugs him in the head, saying, “Not in my movie.” It’s not just a great ending to a horror movie. It’s a big middle finger to sleazy teenage boyfriends the world over.

#7 Crispian, You’re Next

Ooh, when Erin finds out that this rotten man has knowingly brought her along to a home invasion… His attempt to charm (and bribe) her might have won over a weaker person. But in addition to putting her in danger, he has willingly had his family slaughtered for money. Erin won’t stand for that, and her takedown of yet another Toxic Horror Boyfriend is cause for celebration.

#6 Charles, Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan

Charles McCulloch might be one of the nastiest characters in film history. While school administrators are hardly any student’s best friend, his cold cruelty is downright abnormal. How he manages to be simultaneously overbearing and wicked to his niece, Rennie, I’ll never know. But thankfully, Jason Voorhees drowns him in a vat of toxic waste, removing the need to solve that mystery. Not all heroes wear capes. Sometimes they wear hockey masks.

#5 Tyler, The Menu

Up next on the tasting tray of cinema’s worst boyfriends, we have Tyler. He’s not technically Margot’s boyfriend, because she’s an escort he invited to a fancy dinner. But he should still land in the hall of fame. That’s because he brought her despite knowing ahead of time that nobody was meant to leave the restaurant alive. Thankfully, he gets one of the best Bad Boyfriend deaths of them all. He dies at his own hands. By hanging. After being thoroughly humiliated with proof that all the mansplaining in the world can’t make someone a good chef. Delectable.

#4 The Baby, Immaculate

You may remember this kill from my Top 10 Child Deaths article. The ending of Immaculate is (there’s no other word for it) immaculate. Shortly after Sister Cecilia learns that she has been unwillingly impregnated with the son of Christ, she gives birth. Instead of letting the church manipulate her further after violating her body, she smashes that godforsaken thing with a rock. In the process, she sheds years of ingrained doctrine and sets herself free once and for all. This is the ending that Antichrist movies have historically been too cowardly to give us. The fact that this character is a potential messiah makes it that much more cathartic.

#3 Carter, The Final Destination

I mean, come on. This guy is literally credited as “Racist” at the end of the movie. Pretty much every Final Destination movie has an asshole character who you crave to see die. But this epithet-spewing, cross-burning bigot is by far the worst of the bunch.

#2 Dean, Get Out

Racism comes in many forms, as Jordan Peele’s Get Out highlights. The Armitage family’s microaggressions quickly become macroaggressions, more than justifying Chris’ revenge slayings. While this whole portion of the movie is immensely satisfying, Dean’s death might just be the most cathartic. This is because he is killed via the antlers of a stuffed deer head. Chris uses the family’s penchant for laying claim to their prey’s bodies against them with this perfectly violent metaphor.

#1 Adrian, The Invisible Man (2020)

Here we have the final boss of Toxic Horror Boyfriends. This man is so heinously abusive that he fakes his own death in order to torment his ex even more. Cee using his own invisibility suit against him to stage his death by suicide is perfectly fitting revenge.

Editorials

‘Ready or Not’ and the Cathartic Cigarette of a Relatable Final Girl

I was late to the Radio Silence party. However, I do not let that stop me from being one of the loudest people at the function now. I randomly decided to see Ready or Not in theaters one afternoon in 2019 and walked out a better person for it. The movie introduced me to the work of a team that would become some of my favorite current filmmakers. It also confirmed that getting married is the worst thing one can do. That felt very validating as someone who doesn’t buy into the needing to be married to be complete narrative.

Ready or Not is about a fucked up family with a fucked up tradition. The unassuming Grace (Samara Weaving) thinks her new in-laws are a bit weird. However, she’s blinded by love on her wedding day. She would never suspect that her groom, Alex (Mark O’Brien), would lead her into a deadly wedding night. So, she heads downstairs to play a game with the family, not knowing that they will be hunting her this evening. This is one of the many ways I am different from Grace. I watch enough of the news to know the husband should be the prime suspect, and I have been around long enough to know men are the worst. I also have a commitment phobia, so the idea of walking down the aisle gives me anxiety.

Grace Under Fire

Ready or Not is a horror comedy set on a wealthy family’s estate that got overshadowed by Knives Out. I have gone on record multiple times saying it’s the better movie. Sadly, because it has fewer actors who are household names, people are not ready to have that conversation. However, I’m taking up space this month to talk about catharsis, so let me get back on track. One of the many ways this movie is better than the latter is because of that sweet catharsis awaiting us at the end.

This movie puts Grace through it and then some. Weaving easily makes her one of the easiest final girls to root for over a decade too. From finding out the man she loves has betrayed her, to having to fight off the in-laws trying to kill her, as she is suddenly forced to fight to survive her wedding night. No one can say that Grace doesn’t earn that cigarette at the end of the film. As she sits on the stairs covered in the blood of what was supposed to be her new family, she is a relatable icon. As the unseen cop asks what happened to her, she simply says, “In-laws.” It’s a quick laugh before the credits roll, and “Love Me Tender” by Stereo Jane makes us dance and giggle in our seats.

Ready or Not Proves That Maybe She’s Better Off Alone

It is also a moment in which Grace is one of many women who survives marriage. She comes out of the other side beaten but not broken. Grace finally put herself, and her needs first, and can breathe again in a way she hasn’t since saying I do. She fought kids, her parents-in-law, and even her husband to escape with her life. She refused to be a victim, and with that cigarette, she is finally free and safe. Grace is back to being single, and that’s clearly for the best.

This Guy Busick and R. Christopher Murphy script is funny on the surface, even before you start digging into the subtext. The fact that Ready or Not is a movie where the happy ending is a woman being left alone is not wasted on me, though. While Grace thought being married would make her happy, she now has physical and emotional wounds to remind her that it’s okay to be alone.

One of the things I love about this current era of Radio Silence films is that the women in these projects are not the perfect victims. Whether it’s Ready or Not, Abigail, or Scream (2022), or Scream VI, the girls are fighting. They want to live, they are smart and resourceful, and they know that no one is coming to help them. That’s why I get excited whenever I see Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett’s names appear next to a Guy Busick co-written script. Those three have cracked the code to give us women protagonists that are badasses, and often more dangerous than their would-be killers when push comes to shove.

Ready or Not Proves That Commitment is Scarier Than Death

So, watching Grace run around this creepy family’s estate in her wedding dress is a vision. It’s also very much the opposite of what we expect when we see a bride. Wedding days are supposed to be champagne, friends, family, and trying to buy into the societal notion that being married is what we’re supposed to aspire to as AFABs. They start programming us pretty early that we have to learn to cook to feed future husbands and children.

The traditions of being given away by our fathers, and taking our husbands’ last name, are outdated patriarchal nonsense. Let’s not even get started on how some guys still ask for a woman’s father’s permission to propose. These practices tell us that we are not real people so much as pawns men pass off to each other. These are things that cause me to hyperventilate a little when people try to talk to me about settling down.

Marriage Ain’t For Everybody

I have a lot of beef with marriage propaganda. That’s why Ready or Not speaks to me on a bunch of levels that I find surprising and fresh. Most movies would have forced Grace and Alex to make up at the end to continue selling the idea that heterosexual romance is always the answer. Even in horror, the concept that “love will save the day” is shoved at us (glares at The Conjuring Universe). So, it’s cool to see a movie that understands women can be enough on their own. We don’t need a man to complete us, and most of the time, men do lead to more problems. While I am no longer a part-time smoker, I find myself inhaling and exhaling as Grace takes that puff at the end of the film. As a woman who loves being alone, it’s awesome to be seen this way.

The Cigarette of Singledom

We don’t need movies to validate our life choices. However, it’s nice to be acknowledged every so often. If for no other reason than to break up the routine. I’m so tired of seeing movies that feel like a guy and a girl making it work, no matter the odds, is admirable. Sometimes people are better when they separate, and sometimes divorce saves lives. So, I salute Grace and her cathartic cigarette at the end of her bloody ordeal.

I cannot wait to see what single shenanigans she gets into in Ready or Not 2: Here I Come. I personally hope she inherited that money from the dead in-laws who tried her. She deserves to live her best single girl life on a beach somewhere. Grace’s marriage was a short one, but she learned a lot. She survived it, came out the other side stronger, richer, and knowing that marriage isn’t for everybody.