Editorials

Maila Nurmi, Vampira: Transgressive Sexuality & Queer Connections in 1950s America

Vampira and Elvira were not friends. Maila Nurmi, known primarily as Vampira, the original horror hostess of the 1950s, was a complicated, enigmatic, and profound woman. Amid 1950s-era misogyny, Vampira miraculously emerged among the smiling white housewives that plastered homemaking magazines and the objectified, doe-eyed young women in gentlemen’s magazines such as Playboy. Nurmi used these harmful images to her advantage, luring ogling men with her sleek black dress and come-hither voice, then subjecting them to her dominatrix attitude and piercing scream. Not to mention, B horror movies!

“The shock value of Vampira,” explains W. Scott Poole in his book Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror (2014), “came from her refusal to submit to the male gaze. She wanted to attack it instead […]. Vampira represented both homage and satire of the pin-up tradition. Cheesecake came with a heavy dose of gothic morbidity and transformed the sexual politics and imagery of mid-century America into a sandbox she could play in.” Nurmi’s albeit-brief success as a late-night horror hostess on The Vampira Show in the 1950s paved the way for her predecessor, Cassandra Peterson.

Elvira’s Emergence: Cassandra Peterson’s Homage to Vampira

Peterson, known worldwide as the seductive and hilarious Elvira, modeled her Valley Goth Girl horror hostess character after Nurmi’s sexy macabre creation decades earlier. Studio executives advocated this aesthetic decision after Peterson tried first to have her character be more of an homage to the late Sharon Tate. Unfortunately, Nurmi did not appreciate the executives’ directive decision and took Elvira’s eventual stardom as a slap in the face. Despite Peterson’s consistent admiration for Nurmi’s Vampira, Nurmi would never accept Elvira as anything but a knockoff.

However, the women had more similarities than Nurmi may have understood. Not only did both women share a seemingly spiritual bond with Elvis Presley, having both met and shared intimate conversations with the icon nearly a decade apart in Las Vegas, but they have both advocated for the marginalized and have clear connections to the queer community throughout their careers and personal lives. Camp and transgressive sexuality play a central role in their legacies as mistresses of the dark.

Vampira and Elvira’s Impact on the LGBTQ+ Community

Peterson came out publicly as queer in her recent bestselling memoir Yours Cruelly, Elvira: Memoirs of the Mistress of the Dark (2021) after decades of being titillation for male horror fans (of which she lost many after her coming out). Throughout her life, Nurmi interacted with queerness through comics, friendships, and politics. Though we may never know for sure if her queer connections go beyond the platonic and salutatory, we do know that based on her life story, particularly as it is portrayed in Poole’s 2014 book as well as filmmaker R.H. Greene’s 2012 documentary Vampira & Me, she was an ally who inspired countless queer folks to be their authentic, creepy, campy selves. Critics and normals be damned.

From a young age, Maila was unafraid to explore the boundaries of gender expression, particularly in comics and in the theater. Her favorite comic strip, Milton Caniff’s Terry & the Pirates, which debuted in 1934, offered sci-fi adventure mixed with subversion. Her obsession with the villainous character of The Dragon Lady, a Chinese pirate queen, followed her throughout her life and helped to develop her ethos as a performer.

The strip “offered transgressive visions of women and sexuality,” and by 1940, Caniff introduced Sanjak, a villain whose character is named after a Greek island near Lesbos. “Caniff,” explains Poole, “portrayed Sanjak as a French woman who cross-dresses by wearing a men’s uniform and had a monocle…”. Maila would also cross-dress in her high school Rhythm Club performances; one yearbook photo shows her as a vaudevillian “Chaplin-esque looking sailor.”

Vampira’s Bohemian Roots: Greenwich Village and Queer Allies

After graduation, Maila set her sights on New York City’s beatnik enclave of Greenwich Village. There, she associated herself with like-minded dreamers, poets, and activists. One such connection was Harry Hay, the gay communist organizer and founder of the Mattachine Society in 1950. This would not be the only time she associated herself with known queer figureheads and creatives. For instance, Maila debuted the rough draft for Vampira at Lester Horton’s Bal Caribe Halloween extravaganza.

“The Bal Caribe,” Poole states, “represented the most outré gathering in 1950s Hollywood that brought together the city’s gay elite, political radicals, and a hefty portion of campy glamour. Horton had long been part of Hollywood’s gay scene.” Maila would go on to win Best Costume – Vampira found her first audience.

Friends of Vampira, James Dean and Liberace

As her infamy grew with The Vampira Show (1954-1955), she met her “soulmate,” James Dean. Dean, the up-and-coming enigmatic young actor who lit Hollywood ablaze, was the subject of several rumors linking him to queer Hollywood and romantically to Maila, though the infatuation appears to have been one-sided. Dean himself was bisexual, though he never came out publicly. Another closeted Hollywood fixture, Liberace, paled around with Nurmi in Las Vegas in 1956. She joined his flamboyant nightclub act as the “local TV glamour ghoul” though her true role remains unclear. According to Nurmi, at one of Liberace’s performances, an audience member yelled “Liberace is a f**!” Nurmi spat on the heckler.

Ed Wood and Plan 9 from Outer Space

As Vampira/Maila’s star power was being extinguished thanks to the sudden cancelation of The Vampira Show, Maila was approached by B-movie director Ed Wood to star in his low-budget sci-fi alien zombie flick Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959). At this point in his personal life, Wood was known to be a cross-dresser, as alluded to in his semi-autobiographical gender horror flick Glen or Glenda (1953). While Maila in later interviews lambasted Wood’s ability to write dialogue, she accepted the role in Plan 9 for $200 due to financial troubles, which would follow her until she died in 2008.

Vampira vs Elvira: The Legendary Feud

In 1980, following a long drought in her acting career, executives at the cable network KHJ-TV wanted to revamp the horror hostess for a new generation. They approached Nurmi, though they intended to cast someone much younger. Nurmi initially agreed to the project to help find and train a new Vampira. However, she quickly grew disillusioned by the deal after the network supposedly rejected her idea of having either BIPOC actresses Lola Falana or Martine Beswick as the hostess. After Groundlings alum Cassandra Peterson was signed on, and the producers decided she would dress similarly to Vampira, Nurmi felt cheated.

She would go on to sue both Peterson and the producers, but she couldn’t follow through in part due to a lack of funds. “The inventor is rarely honored for anything,” stated Nurmi in Greene’s documentary (2012). “I pity those people,” meaning, the copycats, most likely referring to Peterson. In her autobiography, Peterson describes the situation as unfortunate. Elvira became the most popular horror hostess of the genre, but Peterson insisted she did not mean to insult Nurmi with her spin on Vampira’s original look. It was in the meetings with KHJ-TV executives that Peterson first heard of Vampira, and until then, thought Vampira was just a generic name for a female vampire.

Lola Falana Martine Beswick

Camp, Queerness, and Cultural Subversion

It is interesting how many closeted (and open) queer people Maila Nurmi attracted during her fame. Whether it be her camp sensibilities; her willingness to openly scoff at and reject social norms and gender roles; or her dedication to her role as Vampira, the spookiest, sexiest woman in town; queers felt comfortable in her presence in the hostile environment of 1950s America. Maila’s entire persona and dedication to performance art inspired countless drag looks for decades, including Peterson’s Elvira, a character beloved by the queer community. One can posit that, under less professional circumstances, Cassandra and Maila might have been friends or at least acquaintances, should the drama between the two creatives and the selfish actions of studio executives never occurred.

A Subversive Burlesque of American Culture

History doesn’t repeat: it rhymes. Peterson’s campy Valley Girl/Goth Royalty Elvira was an ode to Nurmi’s satirical Beat Generation ghoul Vampira. Likewise, Charles Addams’s subversive matriarch, The Ghoul/Morticia, inspired Vampira. Each was a variation of the other, all transgressive in their respective periods. “American culture had become a subversive burlesque,” writes Poole, “a sideshow with a sense that performing cultural identity always means some level of love and theft.”

Maila Nurmi’s Enduring Influence: A Queer Icon

Maila Nurmi personifies the power one can wield when being their own eccentric and kooky self. It is no wonder that queer people felt comfortable around her and continue to be inspired by what Vampira stands for. Vampira, for many, was a barren temptress who cared not about your opinions or classifications. It didn’t matter the social mores or gender roles of the period: when Vampira appeared on screen in the L.A. area, she tore up the rulebook and refused to compromise on her art, even when starving and penniless. Queers were transfixed by her one or two years of fame. They, as well as punks and goths, stood by her as her career took a downturn, bringing her food and gigs in her later years. These groups continue to conjure the ghoul goddess through drag. Maila Nurmi will always be a dark icon of the weirdos; her impact is not lost on us queers.

Check out R.H. Greene’s documentary Vampira & Me (2012) on Tubi!

Scott Poole’s book Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror (2014) is available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Soft Skull Press.

Cassandra Peterson’s Yours Curelly, Elvira: Memoirs of the Mistress of the Dark (2021) is available wherever books are sold.

Editorials

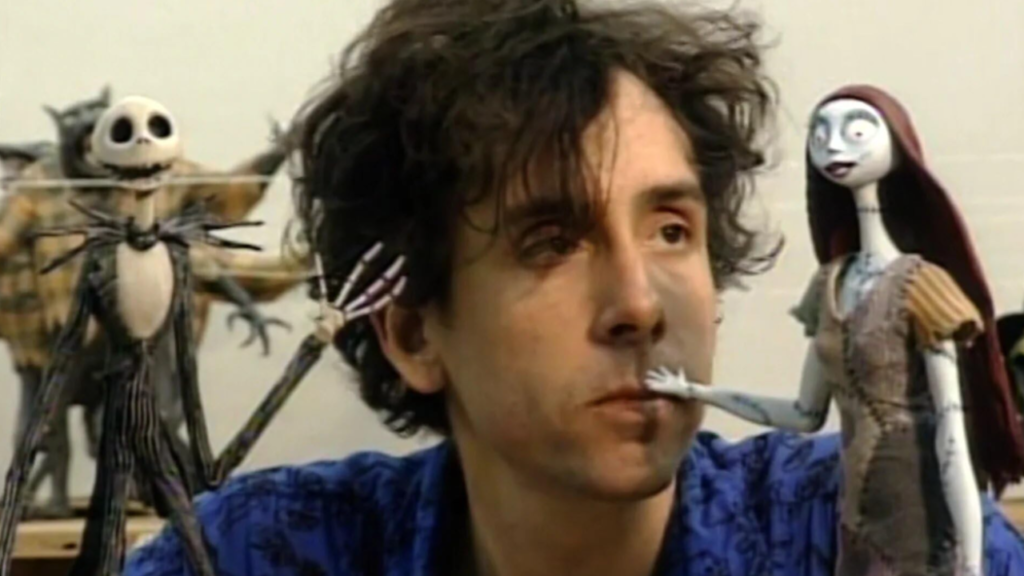

Tim Burton, Representation, and the Problem With Nostalgia

Tim Burton was not always my nemesis. In the not-too-distant past, I was a child who just wanted to watch creepy things. I rewatched Beetlejuice countless times and thought he was a lot more involved in Henry Selick’s The Nightmare Before Christmas than he actually was. I was also a huge Batman fan before Ben Affleck happened to the Caped Crusader. To this day, I still argue that Michael Keaton’s Bruce Wayne was one of the best. So when I tell you I logged many hours rewatching Burton’s better films in my youth, I am not lying.

However, as I got older, I started to realize that this director’s films are usually exclusively filled with white actors. Even his animated work somehow ignores POC actors, seemingly by design. This is sadly common in the industry, as intersectionality seems to be a concept most older filmmakers cannot wrap their heads around. So, I was one of the people who chalked it up to a glaring oversight and not much more. I also outgrew Burton’s aesthetic and attempts at humor when I started seeking out horror movies that might actually be scary.

I Was Over Tim Burton Before It Was Cool

So, how did we get to episodes of the podcast I co-host, roasting Tim Burton? I kind of forgot about the man behind all of those movies I thought were epic when I was a kid. In huge part because his muse was Johnny Depp, whom I also outgrew forever ago. I wasn’t thinking about Burton or his filmography, and I doubt he noticed a kid in the Midwest stopped renting his movies. I didn’t think about Burton again until 2016 rolled around.

In an interview with Bustle for Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, the lack of diversity in Burton’s work came up. That’s when the filmmaker explained this wasn’t a simple blunder or oversight on his part. He also unsurprisingly said the wrong thing instead of pretending he’d like to do better in the future.

Tim Burton said, “Things either call for things, or they don’t. I remember back when I was a child watching The Brady Bunch, and they started to get all politically correct. Like, OK, let’s have an Asian child and a black. I used to get more offended by that than just… I grew up watching blaxploitation movies, right? And I said, that’s great. I didn’t go like, OK, there should be more white people in these movies.” – Bustle

Tim Burton Is Not the Only One Failing

We watch older white guys fumble in interviews when topics like gender parity, diversity, politics, etc., come up all the time. It’s to the point now where most of us are forced to wonder if their publicists have simply given up and just live in a state of constant damage control. However, Tim Burton’s response was surprisingly offensive in so many ways. The more I reread it, the more pissed off at this guy I forgot existed after we returned our copy of Mars Attacks! to the Hollywood Video closest to my childhood home. While I knew I wouldn’t be revisiting Edward Scissorhands and Beetlejuice, his explanation for the almost complete absence of POC in his work burst a bubble.

We Hate To See It

Tim Burton’s own words made me realize so many obvious issues that I excused as a kid. Like Billy Dee Williams as Harvey Dent in Batman, it was the only time I remembered a Black actor with substantial screentime in a Burton film. Or that The Nightmare Before Christmas was really named the late Ken Page’s character, Oogie Boogie. As a Black kid, what a confusingly racist image with a helluva song. So, Burton saying the quiet part out loud is what led me to reexamine the actual reasons I probably stopped watching his work. His problematic answer is also why I don’t have the nostalgia that made most of my friends sit through Beetlejuice Beetlejuice.

I love the cast for this sequel we didn’t need. I am also delighted to see Jenna Ortega continue working in my favorite genre. However, from what I heard from most of my friends who watched the movie, I’m not the only person who has outgrown Tim Burton’s messy aesthetic and outdated stabs at jokes. I am also not the only one paying attention to what’s being said about the Black characters on Wednesday. Again, I’m always happy to see Ortega booked and busy. However, I also refuse to pretend Burton has fixed his diversity problem. If anything, this moves us deeper into specific bias territory.

Tim Burton’s Bare Minimum Is Not Good Enough

He will now cast a couple of Brown people, but is still displaying colorism and anti-Blackness. His “things” seemingly “call for things” that are not Black folks in key roles that aren’t bullies. He still feels that’s his aesthetic. If we are still dragging him into the last millennium, will he ever work on a project that truly understands and celebrates intersectionality? Or will he continue doing the bare minimum while waiting for a cookie? I don’t know, and to be honest, I don’t care anymore. I’m not the audience for Tim Burton. You can say my “things” no longer “call for things” he’s known for. In part because I’m over supporting filmmakers who don’t get it and don’t want to get it.

If a director wants to stay in a rut and keep regurgitating the mediocre things that worked for him before I was born, that’s his business. I’m more interested in what better filmmakers who can envision worlds filled with POC characters. Writer-directors that understand intersectionality benefits their stories are the people I’m trying to engage with. So, while Tim Burton might have had a few movies on repeat during my VHS era, I have as hard of a time watching his work as he has imagining people who look like me in his stuff. I will never unsee “let’s have an Asian child and a black” in his offensive word salad. However, I don’t think he wants me in the audience anyways because he might then have to imagine a world that calls for people who look like me.

Editorials

No, Cult Cinema Isn’t Dead

My first feature film, Death Drop Gorgeous, was often described as its own disturbed piece of queer cult cinema due to its over-the-top camp, practical special effects, and radical nature. As a film inspired by John Waters, we wore this descriptor as a badge of honor. Over the years, it has gained a small fanbase and occasionally pops up on lists of overlooked queer horror flicks around Pride month and Halloween.

The Streaming Era and the Myth of Monoculture

My co-director of our drag queen slasher sent me a status update, ostensibly to rile up the group chat. A former programmer of a major LGBTQ+ film festival (I swear, this detail is simply a coincidence and not an extension of my last article) declared that in our modern era, “cult classic” status is “untenable,” and that monoculture no longer exists. Thus, cult classics can no longer counter-culture the mono. The abundance of streaming services, he said, allows for specific curation to one’s tastes and the content they seek. He also asserted that media today that is designed to be a cult classic, feels soulless and vapid.

Shots fired!

Can Cult Cinema Exist Without Monoculture?

We had a lengthy discussion as collaborators about these points. Is there no monoculture to rally against? Are there no codes and standards to break and deviate from? Are there no transgressions left to undertake? Do streaming services fully encompass everyone’s tastes? Maybe I am biased. Maybe my debut feature is soulless and vapid!

I’ve been considering the landscape. True, there are so many options at our streaming fingertips, how could we experience a monoculture? But to think a cult classic only exists as counter-culture, or solely as a rally against the norm, is to have a narrow understanding of what cult cinema is and how it gains its status. The cult classic is not dead. It still rises from its grave and walks amongst the living.

What Defines a Cult Classic? And Who Cares About Cult Cinema?

The term “cult classic” generally refers to media – often movies, but sometimes television shows or books – that upon its debut, was unsuccessful or undervalued, but over time developed a devout fanbase that enjoys it, either ironically or sincerely. The media is often niche and low budget, and sometimes progressive for the cultural moment in which it was released.

Some well-known cult films include The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), Showgirls (1995), Re-Animator (1985), Jennifer’s Body (2009), and my personal favorite, Heathers (1989). Quoting dialogue, midnight showings, and fans developing ritualistic traditions around the movie are often other ways films receive cult status (think The Rocky Horror Picture Show).

Cult Cinema as Queer Refuge and Rebellion

Celebration of cult classics has long been a way for cinephiles and casual viewers alike to push against the rigid standards of what film critics deem “cinema.” These films can be immoral, depraved, or simply entertaining in ways that counter mainstream conventions. Cult classics have often been significant for underrepresented communities seeking comfort or reflection. Endless amounts of explicitly queer cinema were lambasted by critics of their time. The Doom Generation (1995) by Gregg Araki and John Waters’ Pink Flamingos (1972) were both famously given zero stars by Roger Ebert. Now both can be viewed on the Criterion Channel, and both directors are considered pioneers of gay cinema.

Cult films are often low-budget, providing a sense of belonging for viewers, and are sometimes seen as guilty pleasures. Cult cinema was, and continues to be, particularly important for queer folks in finding community.

But can there be a new Waters or Araki in this current landscape?

What becomes clear when looking at these examples is that cult status rarely forms in a vacuum. It emerges from a combination of cultural neglect, community need, and the slow bloom of recognition. Even in their time, cult films thrived because they filled a void, often one left by mainstream films’ lack of imagination or refusal to engage marginalized perspectives. If anything, today’s fractured media landscape creates even more of those voids, and therefore more opportunities for unexpected or outsider works to grab hold of their own fiercely loyal audiences.

The Death of Monoculture and the Rise of Streaming

We do not all experience culture the same way. With the freedom of personalization and algorithmic curation, not just in film but in music and television, there are fewer shared mass cultural moments we all gather around to discuss. The ones that do occur (think Barbenheimer) may always pale in comparison to the cultural dominance of moments that occurred before the social media boom. We might never again experience the mass hysteria of, say, Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

For example, our most successful musician today is listened to primarily by her fanbase. We can skip her songs and avoid her albums even if they are suggested on our streaming platforms, no matter how many weeks she’s been at number one.

Was Monoculture Ever Real?

But did we ever experience culture the same? Some argue that the idea of monoculture is a myth. Steve Hayden writes:

“Our monoculture was an illusion created by a flawed, closed-circuit system; even though we ought to know better, we’re still buying into that illusion, because we sometimes feel overwhelmed by our choices and lack of consensus. We think back to the things we used to love, and how it seemed that the whole world, or at least people we knew personally, loved the same thing. Maybe it wasn’t better then, but it seemed simpler, and for now that’s good enough.”

The mainstream still exists. Cultural moments still occur that we cannot escape and cannot always understand the appreciation for. There are fads and trends we may not recognize now but will romanticize later, just as we do with trends from as recently as 2010. But I’d argue there never was monoculture in the same way America was never “great.” There was never a time we all watched the same things and sang Madonna songs around the campfire; there were simply fewer accessible avenues to explore other options.

Indie Film Distribution in the Age of Streaming

Additionally, music streaming is not the same as film streaming. As my filmmaking collective moves through self-distributing our second film, we have found it is increasingly difficult for indie, small-budget, and DIY filmmakers to get on major platforms. We are required to have an aggregator or a distribution company. I cannot simply throw Saint Drogo onto Netflix or even Shudder. Amazon Prime has recently made it impossible to self-distribute unless you were grandfathered in. Accessibility is still limited, particularly for those with grassroots and shoestring budgets, even with the abundance of services.

I don’t know that anyone ever deliberately intends on making a cult classic. Pink Flamingos was released in the middle of the Gay Liberation movement, starring Divine, an openly gay drag queen who famously says, “Condone first-degree murder! Advocate cannibalism! Eat shit! Filth are my politics, filth is my life!”

All comedy is political. Of course, Waters was intentional with the depravity he filmed; it was a conscious response to the political climate of the time. So if responding to the current state of the world makes a cult classic, I think we can agree there is still plenty to protest.

There Is No Single Formula for Cult Cinema

Looking back at other cult classics, both recent and older, not all had the same intentional vehicle of crass humor and anarchy. Some didn’t know they would reach this status – a very “so bad, it’s good” result (i.e., Showgirls). And while cult classics naturally exist outside the mainstream, some very much intended to be in that stream first!

All of this is to say: there is no monolith for cult cinema. Some have deliberate, rebellious intentions. Some think they are creating high-concept art when in reality they’re making camp. But it takes time to recognize what will reach cult status. It’s not overnight, even if a film seems like it has the perfect recipe. Furthermore, there are still plenty of conventions to push back against; there are plenty of queer cinema conventions upheld by dogmatic LGBTQ+ film festivals.

Midnight Movies vs. Digital Fandom

What has changed is the way we consume media. The way we view a cult classic might not be solely relegated to midnight showings. Although, at my current place of employment, any time The Rocky Horror Picture Show screens, it’s consistently sold out. Nowadays, we may find that engagement with cult cinema and its fanbase digitally, on social media, rather than in indie cinemas. But if these sold-out screenings are any indication, people are not ready to give up the theater experience of being in a room with die-hard fans they find a kinship with.

In fact, digital fandom has begun creating its own equivalents to the midnight-movie ritual. Think of meme cycles that resurrect forgotten films, TikTok edits that reframe a scene as iconic, or Discord servers built entirely around niche subgenres. These forms of engagement might not involve rice bags and fishnets in a theater, but they mirror the same spirit of communal celebration, shared language, and collective inside jokes that defined cult communities of past decades. Furthermore, accessibility to a film does not diminish its cult status. You may be able to stream Tim Curry as Dr. Frank-N-Furter from the comfort of your couch, but that doesn’t make it any less cult.

The Case for Bottoms

I think a recent film that will gain cult status in time is Bottoms. In fact, it was introduced to the audience at a screening I attended as “the new Heathers.” Its elements of absurdity, queer representation, and subversion are perfect examples of the spirit of cult cinema. And you will not tell me that Bottoms was soulless and vapid.

For queer communities, cult cinema has never been just entertainment; it has operated as a kind of cultural memory, a place to archive our identities, desires, rebellions, and inside jokes long before RuPaul made them her catchphrases repeated ad nauseam. These films became coded meeting grounds where queer viewers could see exaggerated, defiant, or transgressive versions of themselves reflected back, if not realistically, then at least recognizably. Even when the world outside refused to legitimize queer existence, cult films documented our sensibilities, our humor, our rage, and our resilience. In this way, cult cinema has served as both refuge and record, preserving parts of queer life that might otherwise have been erased or dismissed.

Cult Cinema Is Forever

While inspired by John Waters, with Death Drop Gorgeous, we didn’t intentionally seek the status of cult classic. We just had no money and wanted to make a horror movie with drag queens. As long as there continue to be DIY, low-budget, queer filmmakers shooting their movies without permits, the conventions of cinema will continue to be subverted.

As long as queer people need refuge through media, cult cinema will live on.