Interviews

[INTERVIEW] You Can’t Get Rid of ‘The Babadook:’ Jennifer Kent Discusses Her Feature Debut at 10

It’s hard to think of a horror icon from the 2010s that is as instantly recognizable as the eponymous entity in The Babadook, the directorial debut of Aussie filmmaker Jennifer Kent. With his long black coat, top hat, and grinning white face — all styled after Lon Chaney in the lost film London After Midnight — not to mention his memorable name, Mister Babadook is certainly distinctive.

It’s his post-release activities, however, that truly cemented him in the cultural consciousness. After bursting onto the scene at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival, Mister Babadook quickly pivoted from nightmare to meme to LGBTQ+ antihero and then on to Scream(2022) reference, a career trajectory that most horror villains can only dream of.

Yet despite the good fun we’ve had with its big bad over the years, The Babadook still has the power to hold and haunt us. Sitting in a theater in New York City in 2024 watching Amelia (Essie Davis) wrestling with insidious thoughts of murdering her young son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), I found myself suddenly shifting in my seat, gripped with the same unease that chilled me when I first watched the film in Edinburgh a decade prior. There’s a reason that The Babadook made its way into a Scream film. The shadow it cast is long, and we’re still under it.

Kent herself seems quietly pleased about the lasting mark her film has made. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of The Babadook, I sat down with her at Fantastic Fest 2024 for a conversation about influence, Australianness, and getting audiences to care.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and conciseness.

An Interview with The Babadook Director Jennifer Kent

Samantha McLaren: First off, I wanted to say a personal thank you for giving us a goth gay icon. I was Mister Babadook for Pride in 2017.

Jennifer Kent: Oh, I just love all that! It’s hilarious. I don’t think it’s ever going to go away.

SM: No, he’s in the pantheon of gay icons now; we’ve embraced him as our own.

But on a more serious note, The Babadook has become a kind of cultural milestone. People point to it as being at the start of this new era of horror, an era of — and I hate the term — “elevated” horror. But I’m curious what you view as the film’s greatest legacy.

JK: Wow. I don’t know if I can even answer that! I feel so inside it. I think a legacy is something that other people would perhaps be able to tell me.

I feel it’s influence, as in I feel the love for it. When you make a film and it first comes out, it’s all just such a rush and a blur. But now I can see as the film progresses, I feel really proud that it sits within a canon of films that I absolutely adore. I mean, there was a time when I wanted to make films, I hadn’t made a film, and it wasn’t that long ago. And I feel very proud of it, that it’s been embraced the way it has.

SM: One way you know your horror film has made it is when it’s referenced in a Scream movie. How did you first feel when you heard that?

JK: I mean, Scream I watched as a kid, so to have the film reference my film… it’s surreal. As well as The Simpsons and You’re the Worst and other things that have come up. It always tickles me. It’s a lovely moment.

SM: Australian horror as a whole has a reputation for being very intense, very scary, and often very violent. How do you see your film within the landscape of Aussie horror?

JK: Someone brought up the other day that a lot of Aussie horror is about our environment, because we obviously have cities like everywhere else, and quite populated cities, but we also have what they sometimes call the “dead heart,” which is just this huge expanse of desert. And the nature — you know, there’s the running joke that Australia will kill you, and I think a lot of horror from Australia has utilized that so beautifully.

But I think The Babadook is more interior. It’s what’s inside that will kill you, what’s in the house will kill you. Apart from, like, Lake Mungo, which is also a film that’s interior horror, it’s very different to many Australian horrors, like, say, Wolf Creek.

SM: Drastically different sides of the spectrum.

JK: But still somehow with something similar running through them. The Australianness is there.

SM: It’s a very interior film and a highly emotional film. How did you work with the actors to create a space of psychological safety for them to give such intense performances?

JK: I’m just inherently aware of it as an actor. I had five years of actor training, but I’ve acted since I was a child, unprofessionally and then professionally when I went to drama school. And just as a human, I’m a very sensitive person; I will often feel other people’s feelings for them if they’re not feeling them. So I could no more ignore an actor’s feelings or needs in a scene than fly to the moon, because it’s just so important to me. I work out what kind of actor they are and what they need as an actor — whether they want to talk a lot, not talk a lot; whether they’re a feelings person or more analytical — and then I’ll just keep them safe through lots of preparation.

With Noah, that five-year-old boy who turned six during our shoot — he’s a baby, and this is a scary story, so I needed to educate him and inform him about the story as much as I could, [give him] the child version. And then it’s just about protection and empowerment. And the same with Essie, really. Obviously, she’s not as scared, but it’s still about empowerment and protection.

SM: That really comes through.

JK: I hope so.

SM: You’ve spoken a lot in the past about the reaction toward your mother character who is perhaps not delighted about the joys of motherhood. But then you also have Samuel, this child who is intentionally overwhelming, even annoying, but still sympathetic. Was there any backlash to presenting a child like that?

JK: There was a lot of hatred for that character, which disturbed me, to be honest. I think if you look at the arc of the story, yes he’s annoying and deliberately so, because he’s being harassed and terrified by an entity and he’s the only one that can see it, which brings an enormous amount of frustration and rage in him, and fear.

But once he’s drugged, I fear for him. I don’t hate him, I fear for him, because he was telling the truth all along. So the people who really hate Sam as a character all the way through… I don’t know if I want to go around to their house and have dinner with them. [Laughs.]

The film really requires empathy for that little boy. I feel for him.

SM: You need empathy on both sides. You really feel for Amelia going through all this, but Sam is not to blame.

JK: No, and I think as a writer, I always endeavor to tell a story that has compassion for all the characters, even the ones who are almost irredeemable. I did the Cabinet of Curiosities with Guillermo del Toro recently, and the greatest compliment someone gave me on that was when the couple [in Kent’s episode, “The Murmuring”] were having this argument, this person felt he could understand both sides. It wasn’t like “she’s a bitch” or “he’s a bastard.” It was, “I feel for them both, they’re both lost in this argument.”

SM: I wanted to touch on The Babadook’s aesthetic. I know you were influenced by silent films. Are there any other time periods in horror that influence you or that you’d love to pull from for a future film?

JK: For The Babadook, I was really influenced by the Polanski trilogy of horror films in their design, how spare they are, and how meticulously placed they are. I was also impressed with beautiful films like The Innocents, the Jack Clayton film — I’m always impressed by early horror.

I’m looking to make a fantasy horror coming up next, and what I’ll go to in that is paintings. There’s always an influence waiting to be discovered, and that’s the exciting part of it.

SM: I have one last question for you. We talked a little about The Babadook being part of a new wave of horror. In the 10 years since it came out, are there any trends or movements in horror that you find particularly exciting or inspiring?

JK: I think that what’s exciting about this last decade is that films that have depth and complexity and heart to them are actually being financed. And not just being financed — they’re having money thrown at them for P&A [Prints and Advertising].

When The Babadook came out, it wasn’t in this climate where you could put it on in 500 screens. And now it is on 500 screens 10 years later, when originally, it was on two. I think that reflects the confidence that the powers that be — cinemas and financiers and people with money — have in films in the realm of The Babadook that are maybe a bit more complex and frightening.

Thank you to Jennifer Kent for speaking with us.

If it’s in a word or it’s in a look, you should go rewatch The Babadook.

Books & Comics

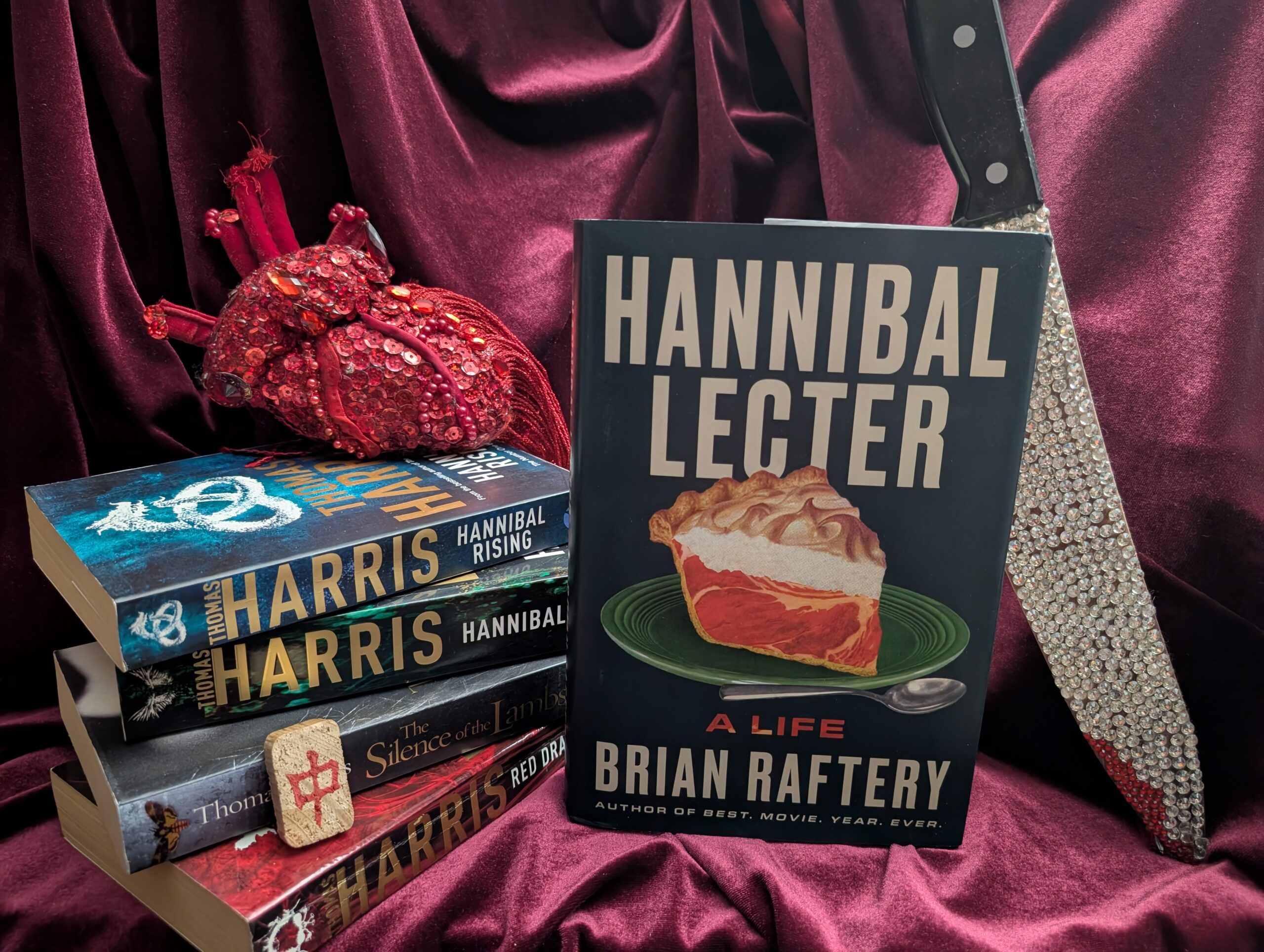

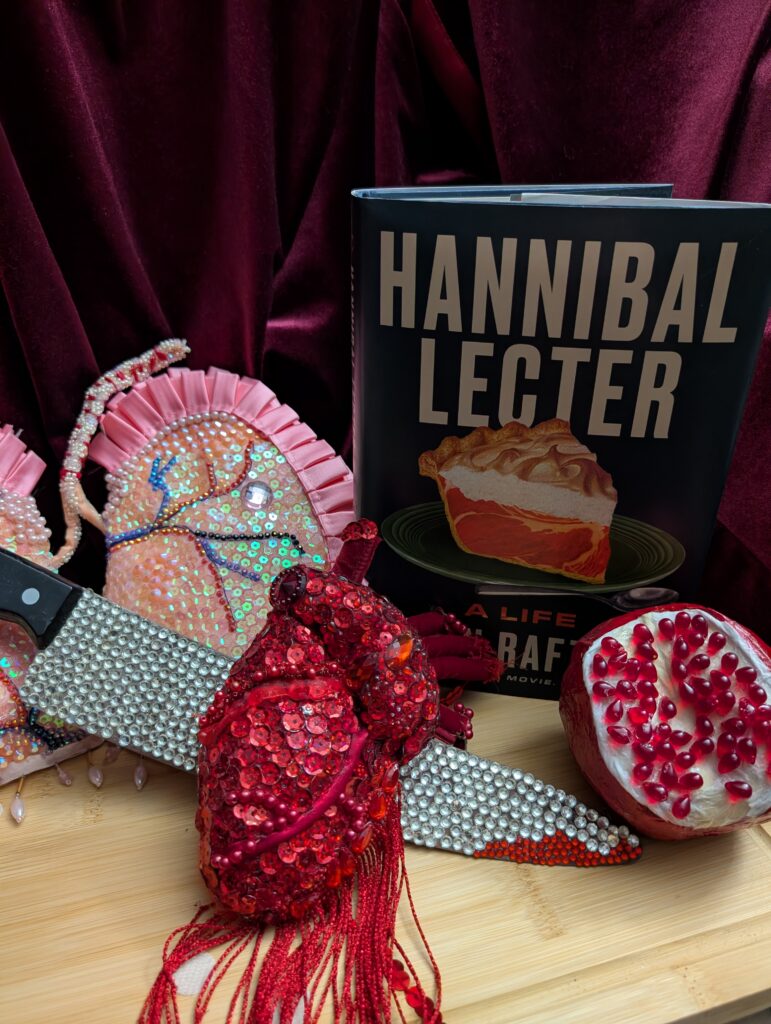

[INTERVIEW] Tucking Into ‘Hannibal Lecter: A Life’ with Author Brian Raftery

If you’ve had so much as a single conversation with me, you’ll know that I am unhealthily obsessed with the television series Hannibal. What you might not know is that I put off watching it when it first aired because I was uncertain it could match the heady thrills of The Silence of the Lambs, one of the first horror movies I ever saw and one that left an indelible mark on me. These pieces of media, along with the Thomas Harris book series upon which they’re based and early adaptation Manhunter, are cornerstones bricks in my psyche as a horror fan. So when Simon & Schuster announced that they were publishing Hannibal Lecter: A Life, I knew I needed to add a copy to my collection pronto.

Author Brian Raftery’s upcoming book is a biography of a character who may not be real, but who has taken on a life that goes far beyond, perhaps, anything his elusive creator ever planned for him. To tell Lecter’s story, Raftery dives into the archives of Silence of the Lambs’ director Jonathan Demme and conducts new interviews with key figures like Manhunter director Michael Mann and actor Brian Cox, the first person to portray Lecter on screen. He also teases out how the rise of Hannibal Lecter as an enduring antihero dovetails with the pop culture-fication of true crime—and considers why a certain politician kept mentioning the “late, great” Hannibal the Cannibal on the campaign trail.

As a self-proclaimed Hannibal Lecter stan (dare I say apologist), I had to get the chef on the phone. The following interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness, and nothing here is vegetarian.

An Early Taste of Hannibal Lecter: A Life With Brian Raftery

Samantha McLaren: Since the book is presented as a biography and you are not a character in it, I want to start with you. What is your personal history with Hannibal Lecter—where did you first encounter him in the wild?

Brian Raftery: The weird thing is, I have a very specific memory of that, which is when The Silence of the Lambs film came out. I was aware of the book—I’d seen some adults that I knew reading it—but I didn’t know what it was about. At that point, I was mostly just reading Stephen King and/or comic books and/or Rolling Stone magazine. And I remember in my eighth grade Spanish class, I was in the back not studying (which I should have been), but I was reading Peter Travers’ review of this movie [in Rolling Stone]. At that point, my horror experience was mostly kind of the classics, like the slasher movies and The Exorcist and The Omen. And I was reading this review and it was a rave, and I was like, wait a minute, this is a respectable, high-end movie about a cannibal. I couldn’t believe this existed, and I was fascinated. I read the review a couple of times.

I didn’t see the movie in the theater—I didn’t see it until it came on VHS. But I was fascinated with it for years; I watched it over and over again. I think when I first watched it, when I was 15 or 16, it was just the shock of Hannibal Lecter and how crazy these kills were. It’s one of those movies that I really remember, as a teenager, the rug being pulled from under me in terms of that ending, where you think they’re going to the house where [Buffalo Bill] is and they changed it up… But then I watched it more and more, and it was one of the first movies that I kind of started to study. It was definitely one of the first commentary tracks I ever heard or owned. They did one really early in the mid-90s when not a lot of people were doing them. And there was so much writing about it and enthusiasm for it in the 90s, it was a movie that never went away throughout the decade.

Then I read the books. I saw Manhunter and read Red Dragon. I was very excited when the Hannibal novel came out. A little less excited when I finally read it. The funny thing is, I missed a lot of the TV show. The TV show came out right after I’d had my first daughter, and I remember putting it on and being like, I can’t watch that. I was just not in the right headspace. That show is amazing to me. I can’t believe the stuff they got away with 10 years or so ago on network television—on NBC of all things, that was airing like Betty White’s competition shows at that point.

So I’ve always been fascinated by the character. He’s just one of the few villains that has never gone away. The character goes away for long stretches because the movies take a while, the books take a while, but [they’re] always circulating somewhere, unlike some horror villains who go in and out of coolness… So when we started talking about the book, I was at first interested in a book on The Silence of the Lambs, and then my editor said, why don’t we look at the Lecter character in general? That spurred the idea of doing a biography about someone who never actually lived.

How Hannibal Lecter Became a Cultural Icon Without Being Everywhere

SM: It’s a great approach because there’s a lot written individually about the different iterations, but less about the Hannibal character as a whole.

BR: The thing that’s so strange… I re-read all the novels when I started working, and it’s still shocking to me how little Hannibal Lecter there is in those first two books. It’s like 12 pages in Red Dragon. It’s wild to me. Even The Silence of the Silence is mostly a Clarice Starling book. And when you get to Hannibal… the first 100 pages is all Clarice Starling again. The fact that he’s remained so popular despite being kind of underexposed is very strange. There are very few characters who have that kind of presence with that little screen or page time for a big chunk of their career, for lack of a better word.

SM: The book reflects that aspect of Hannibal’s character in that he’s obviously the star, but there are times when he takes a back seat while you tell a broader story about the world around him and the lives he’s impacted in some way, in fiction or in real life. Was it difficult to find the right balance there?

BR: It’s interesting because there is so little on Hannibal. Even if you were to write a Wikipedia entry on Hannibal Lecter’s life and background, there’s so little about his personal life in the books until you get to Hannibal and Hannibal Rising. So I went in knowing that you can’t have Hannibal on every page, and at a certain point, I was just as interested in how the culture created and responded to Hannibal Lecter almost more than I was in the character itself, because whether you’re looking through the lens of horror or the bigger cultural impact of him, he’s really unique in the sense that he has a kind of visibility, despite not really being a guy who’s around a whole lot.

When I signed the contract for the book, I think Trump had only mentioned Lecter once or twice. And then, I’m not kidding, like two weeks later my book agent was like, I’m going to stop texting you every time he does it because he’s doing it so often now that I’d be doing it every day. That was kind of confirmation that, okay, these are people who probably haven’t watched the movies or read the books in 30 years… and he’s still an enduring punchline to so many people. Why this character? How can a president talk about Hannibal Lecter in kind of a heroic way in a way you couldn’t talk about Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers? What is it about this guy, and what was his popularity and his ascent? Where did that come from and what does it mean?

SM: There have been so many parodies and references to Hannibal Lecter in everything from children’s movies to Silence! The Musical. Was it a conscious decision to focus on the canonical, official Hannibal versus all the other ways he’s crept out into society?

BR: It’s funny. Two weeks after I turned the book in, I saw a trailer for the new Naked Gun movie last summer that had a Hannibal Lecter joke in it, and I was like oh, I should have waited until that came out! And there was a Variety story a few weeks ago that Zootopia 2 had a whole scene that was going to basically recreate Clarice and Lecter’s encounter from The Silence of the Lambs, which I thought was a pretty funny idea, and they scrapped it because they were like kids won’t have the patience for this and won’t understand it. I’m old enough to remember The Silence of the Hams, the Dom DeLuise parody. At a certain point, I was worried that if I just kept mentioning all the parodies and riffs, it would maybe distract.

I probably could have included a few more, but there were just so many of them. They kind of never stopped. For me, I was much more interested in how the success of The Silence of the Lambs back in 1991 created (along with Se7en) so many serial killer movies. I remember that I saw Copycat, that Sigourney Weaver and Holly Hunter one, at a screening in the mid-90s, and even I was kind of like, you’re gonna call this Copycat and you’re doing a serial killer movie after The Silence of the Lambs? It was just a little on the nose.

Jodie Foster as Clarice Starling, Silence of the Lambs (1991)

SM: There are a lot of Hannibal connections that are widely known at this point, but you also uncovered stories people might not know, like the women agents who helped shape Clarice. Were there any connections or details you uncovered in your research that you were especially excited to share with a wider audience?

BR: I’m totally blunt about this in the book: I could not talk with Tom Harris. He’s given three interviews, I think, in 50 years. But it meant that basically anything I could find about Tom Harris, any scrap, I had to look at it and be like, can I use this?

I was very lucky in that Jonathan Demme, who is the director of The Silence of the Lambs, and who remained friends with Harris even though he didn’t make the Hannibal sequel—his papers are at the University of Michigan. I got to go through and there was a ton of amazing stuff in there. I can’t say enough good things about the University of Michigan. These were random faxes from Tom Harris to Jonathan Demme and the producers, and there’d be little clues in there. At one point, he mentioned the names of some of the FBI agents he spoke to for the books—that’s the golden ticket.

One of them is still alive and I spoke to her for two hours. Her name is Athena Varounis. She’s fantastic, she should have her own book… She was someone who Harris met with repeatedly while writing The Silence of the Lambs. There’s also a woman named Patricia Kirby who Harris met with at least once or twice during the 80s working at the Behavioral Science Unit [who he spoke to about] being a female FBI agent. That stuff was fascinating because I didn’t know any of it, and to find the name of someone he spoke to on a handwritten fax is phenomenal as a reporter.

Even though it’s called Hannibal Lecter: A Life, to me, Clarice is equally important. I don’t think the movie The Silence of the Lambs would have taken off if it weren’t for Clarice Starling. Hannibal Lecter is not interesting to us unless we’re seeing him through Clarice Starling’s eyes, so I wanted to make sure that her story was told and how she came about. I think they’re the most perfect horror couple… It’s not a love affair, but it’s the closest two humans ever come in a movie despite (aside from brushing fingers) never touching each other.

SM: Harris is known for being elusive. If you had been able to speak to him, is there a burning question you were left with from your research that you would have loved the opportunity to ask?

BR: I had to take a lot of things on secondhand accounts or inference. What’s interesting about what serial killers informed Buffalo Bill or Hannibal Lecter is, he’s barely ever spoken on that. I mean, [former Behavioral Science Unit chief] John Douglas and the FBI have theories, and it’s clear when you look at Tom Harris’ relationship with the FBI, the agents he’s talking to and the killers they were studying, there’s connections there.

My big fascination, which is probably not everyone’s question they want to ask Tom Harris, is Hannibal Rising. With the first two movies, he wanted no involvement; he was happy to cash the checks and he would talk to Jonathan Demme if he needed to. They did the Red Dragon remake, and he was kind of involved again. And then, after proclaiming his dislike of Hollywood, he writes this screenplay and the book [for Hannibal Rising] at the same time, which any writer will tell you is a terrible idea. Every agent, every studio executive, they do not want a novelist working on a screenplay at the same time—it’s usually disastrous. The movie and the book were disappointing commercially. I want to know, how much of that was his trying to wrestle back control of the Hannibal character? Because at a certain point, the character becomes bigger than the books. It was hard to write about Hannibal Lecter without people seeing Anthony Hopkins.

I’m kind of fascinated by Hannibal Rising because it’s one of the 2000s’ most interesting failures. There’s very little documentation about. I talked to the director of the movie and found everything I could about it, but Harris did the screenplay and worked on the book—he didn’t do press. He didn’t really coordinate with a lot of people or communicate with a lot of people. So what he was thinking at the time, I can only guess.

Sir Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter, Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Living With a Character Who Never Quite Goes Away

SM: You talk in the book about how engaging with the Hannibal Lecter media has a profound effect on some people, from David Lynch’s revulsion when he was initially attached to adapt Red Dragon to William Peterson feeling like he was Will Graham after filming Manhunter. Did your research and being immersed in this world have an impact on you?

BR: I’ve always been very good about separating fiction. I love the books, I love the movies—I don’t find that material particularly disturbing, but I was also not William Peterson trying to be Will Graham. It’s a different process.

What I found tough was, I’m not a true crime expert. I’ve been interested in true crime in various cases over my life, but for this, I had to really go deep on some serial killers. There were definitely days where I could get up really early and send my kids off to school and be like, I don’t want to deal with Ed Gein. I don’t want to read the Life magazine story about him, I don’t want to go through John Douglas’s FBI photos, but I did. That stuff, after a while, did start to upset me.

Anthony Hopkins went on this long drive from Utah to Pittsburg right before the filming of The Silence of the Lambs, and because he has a steel-trap memory, he at one point named for a reporter every city he stopped in along the way. And I thought, I bet there’s been a serial killer in each one of those cities. I kind of wanted to make that connection between the country he was going across to play this fictitious killer, and we have all these real killers in the country. I had a week where I was just looking through numerous local papers for unsolved murders and cold cases, and a lot of them were really grisly. I remember by Friday I was kind of like, all right, I think it’s time to watch Singing in the Rain.

It was really unpleasant… We think that the world is more violent now, but when you go back to the 60s, 70s, and 80s and go through these newspapers, there’s a lot of really terrible things going on and I didn’t need to know about every single one of them.

SM: Barring the epilogue, the book ends with the conclusion of Hannibal, the TV show. But there have been further adaptations after that, like Clarice [2021, CBS], which doesn’t feature Hannibal but is in his world. How did you decide to end it where you did?

BR: I knew that the TV show was always going to be the last chapter because I knew it was always going to be chronological in terms of where Hannibal Lecter came out. The thing that’s so remarkable to me about Hannibal the TV show is the fact that Bryan Fuller had this many episodes. He planned for many seasons and the ending they had was the ending they had to do—the show was canceled after three seasons. And it’s one of the best endings for a TV show. This could be the end of the show, or the show could have started again three months later and picked up from there.

I like the ambiguity. The idea of Hannibal falling off a cliff and you’re not entirely sure what happened to him is kind of like the ending of The Silence of the Lambs where Hannibal Lecter goes into the crowd. I wanted the book to end with Hannibal Lecter still out there in some way. It’s a biography of a character, and a character who’s still alive, not the “late, great.”

I did talk to Bryan Fuller a bit about how he would like to do a Silence of the Lambs TV series, and he’s talked about it in other interviews, but I didn’t want to speculate. I want to end with what we know about. What we know is he falls off the cliff, and there’s that coda which, of course, implies something else going on. But I like the idea that after that show went off the air, the way that Hannibal Lecter has lived in the last 10 years is in the culture somewhere. He pops up in strange places—he pops up in a Trump speech; he pops up in college courses. It’s almost like you’re waiting for him to come back in from the cold.

For all I know, Tom Harris could have another Hannibal Lecter book, because he’s surprise released almost all of these books. Maybe he’ll do it again. Maybe they’ll figure out the rights situation and who owns what and make another movie or TV series. A couple of people have asked me like, aren’t you afraid they’re going to reboot it? It’s a pretty durable character… It’s the kind of character that you can play a lot of different ways and interpret a lot of different ways.

SM: So what you’re saying is, there might be a second edition in 10 years if Harris surprise drops Hannibal V.

BR:At the least, we’ll have to do a couple of chapters.

Hannibal Lecter: A Life by Brian Raftery hits shelves on February 10. Learn more, including where to pre-order the book and upcoming appearances from Raftery, by visiting Simon & Schuster’s website.

Photo taken by Samantha McLaren.

Film Fests

Inside the Live Scoring of Häxan: An Interview with The Flushing Remonstrance at Brooklyn Horror Film Festival

If I ever needed more proof that Brooklyn Horror Film Festival was the place to be in October, my experience at this year’s live screening of Häxan with The Flushing Remonstrance was that.

The Nitehawk Cinema in Williamsburg is the primary home for the festival, and the host to what feels like a million different screenings. Each film feels like an outpouring of a director’s vision, of a cast and crew’s hard work over months, or even years. But one screening in particular among the repertory options on offer caught my eye, and that was Häxan. Part historical analysis, part horror, and part drama, there aren’t many films like this silent feature from Benjamin Christensen. And certainly, there are very few like it in terms of its age and impact: the movie is over a century old and still manages to grasp the intrigue, imagination, and emotion of audiences today.

But it was what was attached to the film that really intrigued me. Because this particular screening of Häxan was being played with a live accompaniment. I didn’t know what to expect from a group called The Flushing Remonstrance; frankly, I didn’t even know what to expect from a soundtrack accompanying a century old film as unique as Häxan. A set of percussion machines and a keyboard set were set up at the foot of the theatre screen, and soon two musicians approached them: Catherine Cramer and Robert Kennedy, the duo that makes up The Flushing Remonstrance.

The theatre dims, and the soft glow that comes off the lights illuminating their instruments becomes pronounced. The duo’s work blends into the film seamlessly. Their music is introspective, emotionally fine-tuned, and sonically bonded to what’s happening on screen with a level of smoothness I didn’t expect. There was a clear interplay at work between the film and the live score, and I knew then that I had to ask them how they did it. The Flushing Remonstrance was kind enough to entertain the question and spoke with us here at Horror Press about their process and history.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and conciseness.

An Interview With The Flushing Remonstrance on the Art of Live Scoring a 100+ Year Old Film

Luis Pomales-Diaz: So. Why exactly did you name yourselves The Flushing Remonstrance? I don’t want to assume you represent the Quakers, but… the name does raise questions.

Robert Kennedy: We were both working at a museum in Flushing, Queens, when we met. We got together for what we thought would be a one-off show. We would be live scoring vintage cartoons in a park. So, we needed a name, and after the usual process where we came up with a bunch of jokey names that would never fly, we landed on The Flushing Remonstrance.

Mainly because of geographical proximity, and it always sounded kind of ’60s like Jefferson Airplane. It wasn’t a particular political statement, although what the document represented and what they were doing, speaking truth to power, does resonate with us. We claim no representation of Quakers.

Tell us about your musical background. How does it factor into your live performances scoring films?

Catherine Cramer: We get asked a lot, almost every show, ‘how do you do this?’ and ‘is this a composed score or is this entirely improvised?’ And I find it interesting, because I spent the bulk of my musical career playing jazz, and I ask people if they know how that works first.

There’s the chart, a melody that can be written down, but then the bulk of what jazz musicians do varies from performance to performance. Who knows how many iterations of Autumn Leaves there have even been, but they all have their own measure of changes and improvisations.

Robert: We’ve been playing together for ten years, and we bring our improvisational ability and sensibility to [live scores] as our own thing. We’ve almost always played in the context of accompanying a film or a short film. If we hit something while we’re in rehearsal, we’ll run with it. But we don’t have written melodic content like a jazz quartet. Maybe like five percent of our material is identified pitches or chords, and those are primarily to ensure that Catherine’s percussion has a number of sounds that have tonal components, and that we produce either a consonant or dissonant effect.

The best way to describe it is: we are improvised, but we have defined the structure for a given film very precisely. As far as what sorts of sounds and feelings and what sorts of timing will accompany different sections and scenes of a film, it’s definite.

An excerpt from the Flushing Remonstrance live score for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

And when you’re determining those feelings, that framework, what’s the process you go through? How many times do you watch the film through?

Robert: It’s somewhat of an automatic process at this point. We identify a film we want to play, we watch it through (separately, usually), and sort of chart out the architecture of it, almost like a storyboard. Scene by scene, where the scene is taking place, and what’s happening.

We then run the film together, and let the film guide our decisions when we rehearse. And whatever the filmmaker is suggesting to us, that’s what we do. Some films we’ve had to slave over a little bit more, sometimes, we’re particularly satisfied with the first go through. We have a great deal of instrumental rapport that factors into it, and we do it in a way that feels natural to us. So sometimes it comes easily.

Catherine: When we first run through a new film, like with Häxan, there’s a lot of stopping and going back, trying variations of the same scene. Each time through, we change or add something new. And even with the film we’ve played the most, Nosferatu, it’s always different. People come up who have seen us before to tell us our performance had a completely different feeling. It keeps the performances very alive in a sense, even when the film is somewhere around 100 years old.

What causes the variation between screenings of a film like Nosferatu that makes it so different each time, even after a decade of playing the film? What keeps changing, and why?

Catherine: No matter how many times we’ve played Nosferatu, there’s been a continual change. Sometimes it’s an instrumental change. On the Roland Octapad, the instrument that I play, there are a hundred different patches, and in each patch there are eight pads, and in each pad there’s up to as many as four sounds depending on where you hit it. Not including the volume and how you balance the sounds. And that causes radical changes in itself.

How we react to the film emotionally has changed a lot since the very beginning. We watch these films intently, and they guide us not just when we’re coming up with the framework. It guides us when we’re playing. We’re not just playing along but really bonding the music to the film. The last time we played it, it felt more sparse, more haunting.

And playing Nosferatu now, what emotions do you play to the most? What stands out to you more now than when you first started?

Catherine: With Nosferatu…it’s so sad. Nosferatu is a film I see as pathetic, in the truest sense of the word pathos. Orlok is such a tragic figure, and that sense has only grown each time we play it. In certain moments, when the man is walking down the middle of the street reading off the names of the dead during the plague, and every moment when Ellen is sitting by the ocean waiting for her husband to come home, all of the imagery strikes me so much more deeply. It’s those feelings that I’ve tried to accentuate.

Does the audience’s feelings factor into the performance to an extent?

Robert:The feel of the space, the sound of the room, but especially the feel of the crowd, are vital to how these performances keep changing. When we played Todd Browning’s The Unknown and Dali’s Un Chien Andalou in early November of last year, obviously, the presidential election had happened. Any audience we were playing for had that circulating in their head.

There were high emotions and clouded minds, and it was palpable. We brought into it an anger and intensity to a certain extent, because we were putting our own state of mind and our audience’s state of mind into it. Disorientation, paranoia, gloom, it made its way into the music. That’s how it is with improvised music often, you hear more traditional jazz, and you can tell when someone is having a bad night or if they’re sick. You’re not immune to being influenced by outside forces, and in our case, we lean into those outside forces.

A segment of the Flushing Remonstrance’s Nosferatu live score.

As musicians, you have about as many tools as filmmakers when it comes to communicating emotions through your music. Sometimes you even have more, depending on your instruments. Which emotions on film are the most challenging to communicate through your music?

Robert: I think a particular challenge is if there is a sustained scene of intensity. Sustained scenes of violence, a riot, a mob fleeing like in Metropolis. The end of The Phantom of the Opera is another great example, when they’re chasing him through the streets of Paris. The obvious approach is to pile it on, get really loud and clangorous. But after a while, it gets tiring for us and for the audience. You can’t put more water in a full glass. Those are the most challenging, assuring there’s a sense of dynamism while retaining that kinetic feeling. The goal is to maintain the integrity of the film we’re working with.

Catherine: The hardest for me are the spots where there is no emotion. In Nosferatu, we have this scene where the longshoremen are preparing the ship, we have a man reading off a list, men moving boxes, but really not much is happening. You can’t just have it be silent! It’s not until they dump out the dirt and the rats come out that you have something to do. But you can’t leave that dead air, which is hard to fill out. Playing to emotion isn’t necessarily easy because you want to do it well, but it’s the in between parts that get me. And silent films need to have in between parts because you can’t just have constant exposition.

Robert: I immediately thought of the Spanish language version of Dracula we did last year at Brooklyn Horror. There are these long drawing room scenes where they’re sort of just…talking. And like…well, there’s only so much we can do. And that film has a lot of it! (laughs) But then you also have very active characters like that version’s Renfield, who is really just chewing the scenery.

Oh, I truly love Pablo Alvarez Rubio as Renfield. He’s my favorite Renfield. The definitive one for me, I’d love to see what you play for him.

Robert: You know, I have to put in a vote for Tom Waits in Francis Ford Coppola’s version. Beyond the freakishness, he plays so well, there’s this sadness and desperation, being aware he’s a prisoner to Dracula, that’s great. On that note though, there is one thing we do the same every single time when we play Nosferatu.

After Orlok dies in the sunlight, it cuts to Knock in his cell looking out the bars, and he says, ‘The master is dead!’ And we always go to silence, every time. Because the death isn’t the climax, the climax is the aftermath. The spell has been broken, and the sacrifice Lucy has made for this guy…who in like, none of the films, really deserves it! And the silence punctuates that.

The Flushing Remonstrance original score for the Guy Maddin short Blue Mountains Mystery Séance.

For Häxan in particular, you do have quite a few scenes that are high intensity, and high emotion. The film is effectively a witchhunter’s manual, with all the historical cruelty that implies towards the women who are accused witches.

Robert: Absolutely! It’s based at least in part on the Malleus Maleficarum, an actual witchhunter’s manual.

It also has some generally raucous scenes of the witches. The black sabbath in the woods for instance. It’s an easy out to compose something quick and aggressive for that sequence. How did you determine what you wanted to do for that?

Catherine: It’s not an easy film to accompany. There are protracted scenes of torture, scenes of the accused women being interrogated and psychologically beaten down. One of the hardest there is the scene of the priest trying to force the young woman to use magic, to agree to show him so she can see her child again. It’s intense, but there’s subtlety you have to play for.

Robert: You know when that particular scene comes along, you’d think because of the nature of it you’d expect it to call for a big Rite of Spring, grand guignol, kind of raucous sound. But you have to break down where a scene starts and what it is. When it begins, we start with people sitting on a hilltop, and they see the witches flying off to the woods, and then you get the scene of the witches flying over the town. There’s not really fear or aggression in that, but rather mystery and a bit of wonder. So, we play towards that.

Then they get to the woods, and it begins, and that mass the witches start up is at its core a ritual. The question at the heart of it is ‘what sounds like ritual music?’, so we aim for something ritualistic. Someone’s instinct might be to play something like Carmina Burana, but it’s just not interesting. It’s obvious. It isn’t in the interest of the film or our interest to make it noisy or heavy or Stravinsky-esque, because that’s just not what the film is going for.

Häxan is over 100 years old. Though it has the indelible place in horror history, the story it tells and its cinematography, do feel very divorced from modern filmmaking. Is there an emotional disconnect from the way it’s presented that makes putting together the framework you work off of difficult?

Catherine: It’s a fun challenge, and a very different kind of challenge. It’s like a PhD dissertation turned into a film, which is not even factoring in the temporal quality that makes it so different on its own. It’s a shocking film, beyond the content but also shocking in the historicity of it and the sheer number of people killed and tortured in the name of stopping witches. Between 35 and 60 thousand dead. Like really? How many people died for this?

Then there’s also the fact that he brings in contemporary feminism into the film is fascinating, and tragic. Things are somewhat different a century later, but we’ve not completely moved past which is sad.

The film in its last quarter is agonizing. The dialogue it has on the concept of hysteria, and modern psychological medicine as opposed to contemporary notions of psychology…

Robert: I mean the fact that they call it hysteria tells you quite a bit…

Yeah, It’s not great. Interesting, compelling, but flawed in some ways.

Robert: In terms of trying to score a film that’s that old…we try our hardest not to let it change what we do. We take each film on its own level and try to be inspired by it. But we deliberately try not to make any attempt to emulate the music of the period. We avoid idioms, we try to avoid period music because it would be silly just trying because we are primarily using electronic instruments. Whenever it’s possible, it’s just us and the film.

The Flushing Remonstrance plays a live score for the Guy Maddin short “Saint, Devil, Woman”, part of his installation art piece Seances.

How has your approach to live scoring films affected your experience while watching film?

Catherine: I think my history with film itself influences it. I did film studies at NYU, then I worked for Millennium Film Archive for a while, which was a really fabulous place on East 4th Street that preserved avant-garde films. Then I was a film editor for about six years. All that to say, I’ve always been very conscious of the sound in films. I orient more to listening for that. Starting with the sound more than I’m seeing picture wise.

Robert: I come to it from a similar place. My background is a lot of audio production for records. Mix and loudness are key factors, and I can’t turn it off. If a score is too busy or feels cliché or gets in the way of the film, I just can’t ignore it.

Are there any films in particular that you would specifically like to live score in the future?

Robert: Absolutely. We luckily have a good long running relationship with Brooklyn Horror Film Festival, and the yearly festival theme guides us on what we’re doing next year. There’s been a lot of enthusiasm in us reviving our accompaniment to F.W. Murnau’s Faust, but this time with a completely different sound. We won’t retain anything from before, we haven’t played it since 2018, so this will be entirely new. It will have a bit of resonance with Häxan we suspect. There’s a Scandinavian film called The Phantom Carriage that has been on my short list as a film I’ve wanted to play for a long, long time.

We also love working directly with directors. We’ve been very fortunate to work with the filmmaker Guy Maddin, who makes contemporary films that are like silent films. Given our repertoire, we go together very well, and we’re very fortunate to have linked with a living filmmaker. We recently scored two very early Clive Barker films this past summer, one of which has never had a score. We contacted him, and he gave us his blessing. All that said, there’s not a formal list, but we know which films work with how our process and our style work, and we are excited to play them.

Catherine: I always look forward to working with contemporary working filmmakers. And because of our background in avant-garde film, we’ve also been approached to score contemporary short films, and that’s been fun. There are so many different opportunities we’d like to score for. It’s New York, there’s always stuff happening.

Robert: And if you are a contemporary filmmaker who thinks your film would benefit from the sonic ministrations of a group like ours, get in touch with us!

A big thanks once more to The Flushing Remonstrance, who took the time to talk with us. You can follow their ongoings and adventures in live scoring on Instagram. A special thanks also to Brooklyn Horror Film Festival for connecting us.

And finally, thank you for taking the time to read this. Remember to stay tuned to Horror Press (@horrorpressllc on Twitter and Instagram, @horrorpress.com on Bluesky) for more interviews with creatives in the horror space, and for all news horrors!