It’s hard to think of a horror icon from the 2010s that is as instantly recognizable as the eponymous entity in The Babadook, the directorial debut of Aussie filmmaker Jennifer Kent. With his long black coat, top hat, and grinning white face — all styled after Lon Chaney in the lost film London After Midnight — not to mention his memorable name, Mister Babadook is certainly distinctive.

It’s his post-release activities, however, that truly cemented him in the cultural consciousness. After bursting onto the scene at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival, Mister Babadook quickly pivoted from nightmare to meme to LGBTQ+ antihero and then on to Scream(2022) reference, a career trajectory that most horror villains can only dream of.

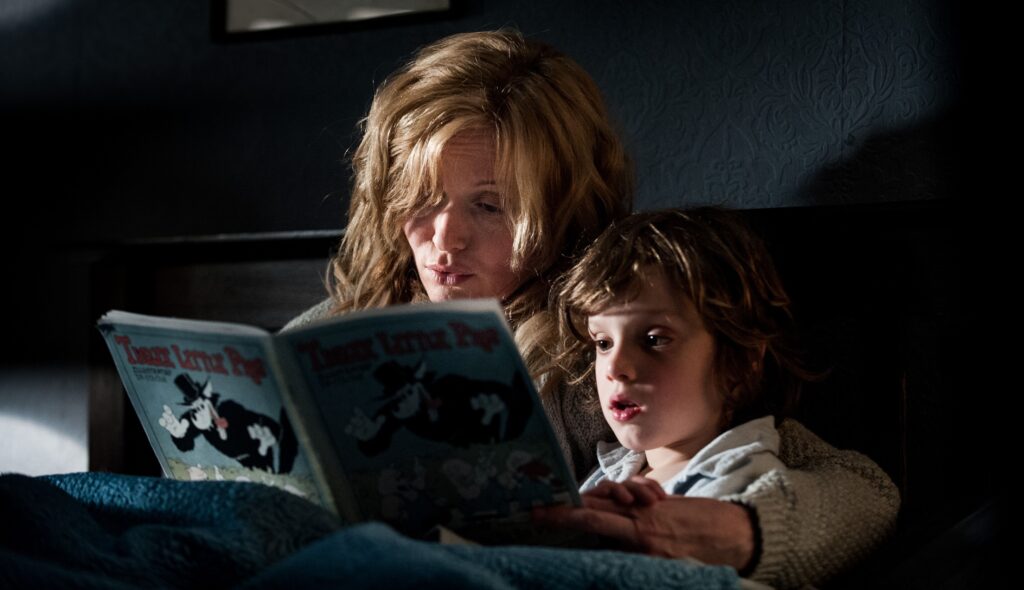

Yet despite the good fun we’ve had with its big bad over the years, The Babadook still has the power to hold and haunt us. Sitting in a theater in New York City in 2024 watching Amelia (Essie Davis) wrestling with insidious thoughts of murdering her young son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman), I found myself suddenly shifting in my seat, gripped with the same unease that chilled me when I first watched the film in Edinburgh a decade prior. There’s a reason that The Babadook made its way into a Scream film. The shadow it cast is long, and we’re still under it.

Kent herself seems quietly pleased about the lasting mark her film has made. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of The Babadook, I sat down with her at Fantastic Fest 2024 for a conversation about influence, Australianness, and getting audiences to care.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and conciseness.

An Interview with The Babadook Director Jennifer Kent

Samantha McLaren: First off, I wanted to say a personal thank you for giving us a goth gay icon. I was Mister Babadook for Pride in 2017.

Jennifer Kent: Oh, I just love all that! It’s hilarious. I don’t think it’s ever going to go away.

SM: No, he’s in the pantheon of gay icons now; we’ve embraced him as our own.

But on a more serious note, The Babadook has become a kind of cultural milestone. People point to it as being at the start of this new era of horror, an era of — and I hate the term — “elevated” horror. But I’m curious what you view as the film’s greatest legacy.

JK: Wow. I don’t know if I can even answer that! I feel so inside it. I think a legacy is something that other people would perhaps be able to tell me.

I feel it’s influence, as in I feel the love for it. When you make a film and it first comes out, it’s all just such a rush and a blur. But now I can see as the film progresses, I feel really proud that it sits within a canon of films that I absolutely adore. I mean, there was a time when I wanted to make films, I hadn’t made a film, and it wasn’t that long ago. And I feel very proud of it, that it’s been embraced the way it has.

SM: One way you know your horror film has made it is when it’s referenced in a Scream movie. How did you first feel when you heard that?

JK: I mean, Scream I watched as a kid, so to have the film reference my film… it’s surreal. As well as The Simpsons and You’re the Worst and other things that have come up. It always tickles me. It’s a lovely moment.

SM: Australian horror as a whole has a reputation for being very intense, very scary, and often very violent. How do you see your film within the landscape of Aussie horror?

JK: Someone brought up the other day that a lot of Aussie horror is about our environment, because we obviously have cities like everywhere else, and quite populated cities, but we also have what they sometimes call the “dead heart,” which is just this huge expanse of desert. And the nature — you know, there’s the running joke that Australia will kill you, and I think a lot of horror from Australia has utilized that so beautifully.

But I think The Babadook is more interior. It’s what’s inside that will kill you, what’s in the house will kill you. Apart from, like, Lake Mungo, which is also a film that’s interior horror, it’s very different to many Australian horrors, like, say, Wolf Creek.

SM: Drastically different sides of the spectrum.

JK: But still somehow with something similar running through them. The Australianness is there.

SM: It’s a very interior film and a highly emotional film. How did you work with the actors to create a space of psychological safety for them to give such intense performances?

JK: I’m just inherently aware of it as an actor. I had five years of actor training, but I’ve acted since I was a child, unprofessionally and then professionally when I went to drama school. And just as a human, I’m a very sensitive person; I will often feel other people’s feelings for them if they’re not feeling them. So I could no more ignore an actor’s feelings or needs in a scene than fly to the moon, because it’s just so important to me. I work out what kind of actor they are and what they need as an actor — whether they want to talk a lot, not talk a lot; whether they’re a feelings person or more analytical — and then I’ll just keep them safe through lots of preparation.

With Noah, that five-year-old boy who turned six during our shoot — he’s a baby, and this is a scary story, so I needed to educate him and inform him about the story as much as I could, [give him] the child version. And then it’s just about protection and empowerment. And the same with Essie, really. Obviously, she’s not as scared, but it’s still about empowerment and protection.

SM: That really comes through.

JK: I hope so.

SM: You’ve spoken a lot in the past about the reaction toward your mother character who is perhaps not delighted about the joys of motherhood. But then you also have Samuel, this child who is intentionally overwhelming, even annoying, but still sympathetic. Was there any backlash to presenting a child like that?

JK: There was a lot of hatred for that character, which disturbed me, to be honest. I think if you look at the arc of the story, yes he’s annoying and deliberately so, because he’s being harassed and terrified by an entity and he’s the only one that can see it, which brings an enormous amount of frustration and rage in him, and fear.

But once he’s drugged, I fear for him. I don’t hate him, I fear for him, because he was telling the truth all along. So the people who really hate Sam as a character all the way through… I don’t know if I want to go around to their house and have dinner with them. [Laughs.]

The film really requires empathy for that little boy. I feel for him.

SM: You need empathy on both sides. You really feel for Amelia going through all this, but Sam is not to blame.

JK: No, and I think as a writer, I always endeavor to tell a story that has compassion for all the characters, even the ones who are almost irredeemable. I did the Cabinet of Curiosities with Guillermo del Toro recently, and the greatest compliment someone gave me on that was when the couple [in Kent’s episode, “The Murmuring”] were having this argument, this person felt he could understand both sides. It wasn’t like “she’s a bitch” or “he’s a bastard.” It was, “I feel for them both, they’re both lost in this argument.”

SM: I wanted to touch on The Babadook’s aesthetic. I know you were influenced by silent films. Are there any other time periods in horror that influence you or that you’d love to pull from for a future film?

JK: For The Babadook, I was really influenced by the Polanski trilogy of horror films in their design, how spare they are, and how meticulously placed they are. I was also impressed with beautiful films like The Innocents, the Jack Clayton film — I’m always impressed by early horror.

I’m looking to make a fantasy horror coming up next, and what I’ll go to in that is paintings. There’s always an influence waiting to be discovered, and that’s the exciting part of it.

SM: I have one last question for you. We talked a little about The Babadook being part of a new wave of horror. In the 10 years since it came out, are there any trends or movements in horror that you find particularly exciting or inspiring?

JK: I think that what’s exciting about this last decade is that films that have depth and complexity and heart to them are actually being financed. And not just being financed — they’re having money thrown at them for P&A [Prints and Advertising].

When The Babadook came out, it wasn’t in this climate where you could put it on in 500 screens. And now it is on 500 screens 10 years later, when originally, it was on two. I think that reflects the confidence that the powers that be — cinemas and financiers and people with money — have in films in the realm of The Babadook that are maybe a bit more complex and frightening.

Thank you to Jennifer Kent for speaking with us.

If it’s in a word or it’s in a look, you should go rewatch The Babadook.